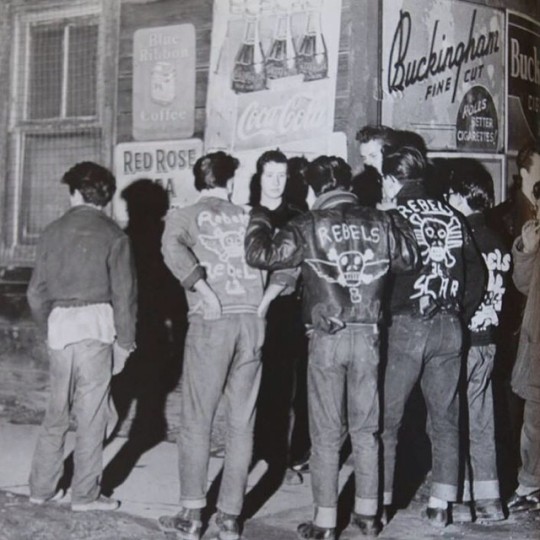

A lot has been written about how clothes have become disassociated from our social identities. A generation ago, you could read someone’s social standing on their sleeve. Mods wore slim fitting suits with short jackets and narrow lapels; counterculture hippies repurposed military service jackets to serve their anti-war aims, treating clothes as political commentary. Even as recent as the 1990s, punks, skaters and goths had very defined ways of dressing – ways that you couldn’t easily adopt without being “authentically” part of the tribe.

A few years ago, The Guardian had an article about how youth subcultures are losing their distinct uniforms, as everyone is just dressing in the same vaguely hip ways. Whatever your musical interest, you probably wear slim jeans with a t-shirt or button-down. The Guardian posits one possible reason: “we now live in a world where teenagers are more interested in constructing an identity online than they are in making an outward show of their allegiances and interests.” Who knows if that’s true, but you don’t see social tribes on the street nowadays in the same ways you did in the 1960s through ‘90s. It’s hard to tell someone’s musical tastes or political leanings just through their clothes.

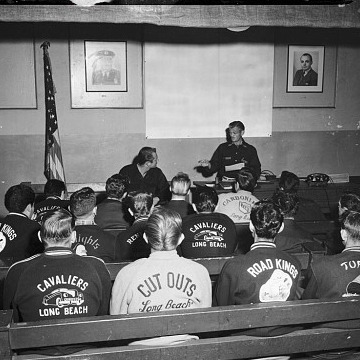

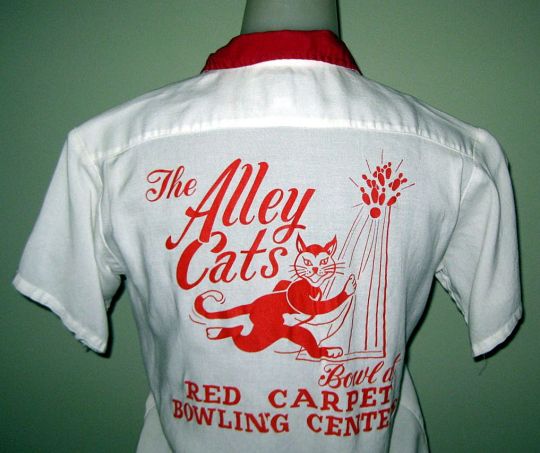

When it comes to tribal clothing, no area of American life has used it more directly than social clubs. Meaning, the kind of matching jackets or shirts that members of the same club used to wear to social gatherings. And at one point, social clubs formed the backbone of American civic life. The World Almanac lists over 2,300 groups with some kind of national visibility – from the Aaron Burr Society to Boy Scouts, Elvis Presley Burning Love Fan Club to Southern Appalachian Dulcimer Association. To be sure, not all of these groups have club clothes – and some of them are little more than organizational equivalents of vanity press publications – but member jackets were often an important part of what it meant to belong to such things, whether they centered on religion, sports, politics, or other interests.

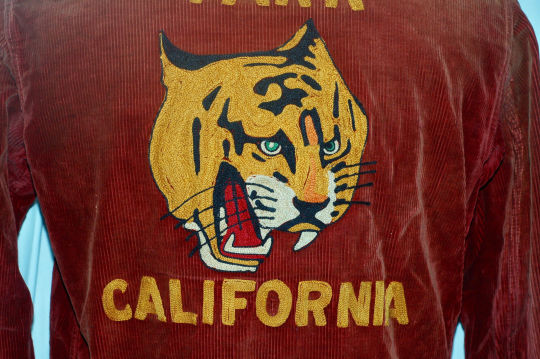

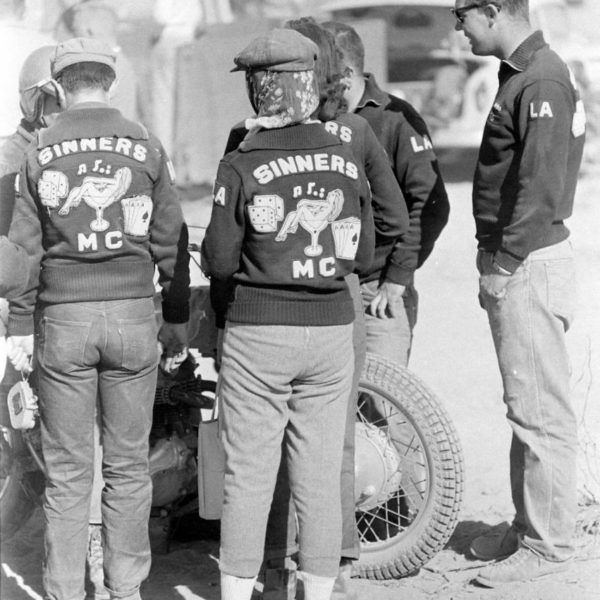

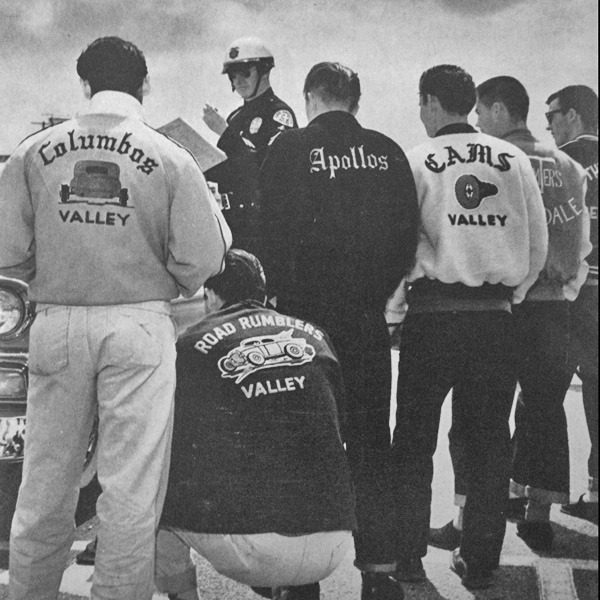

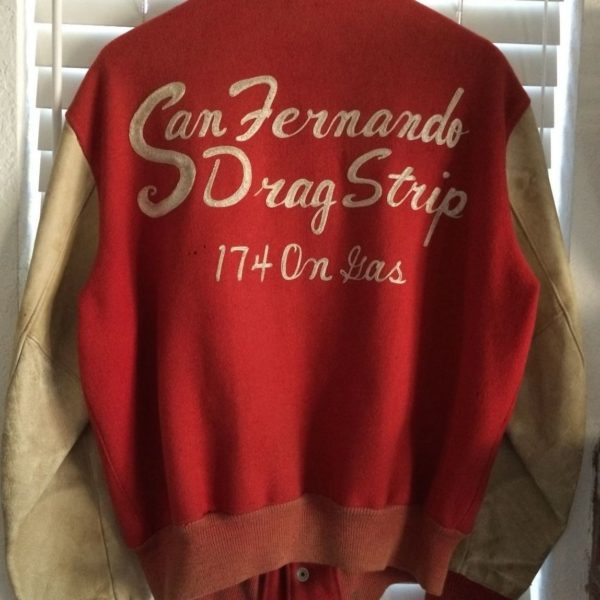

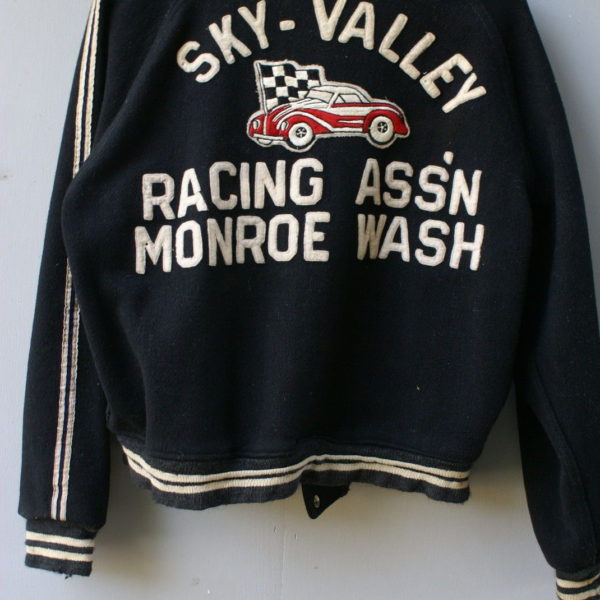

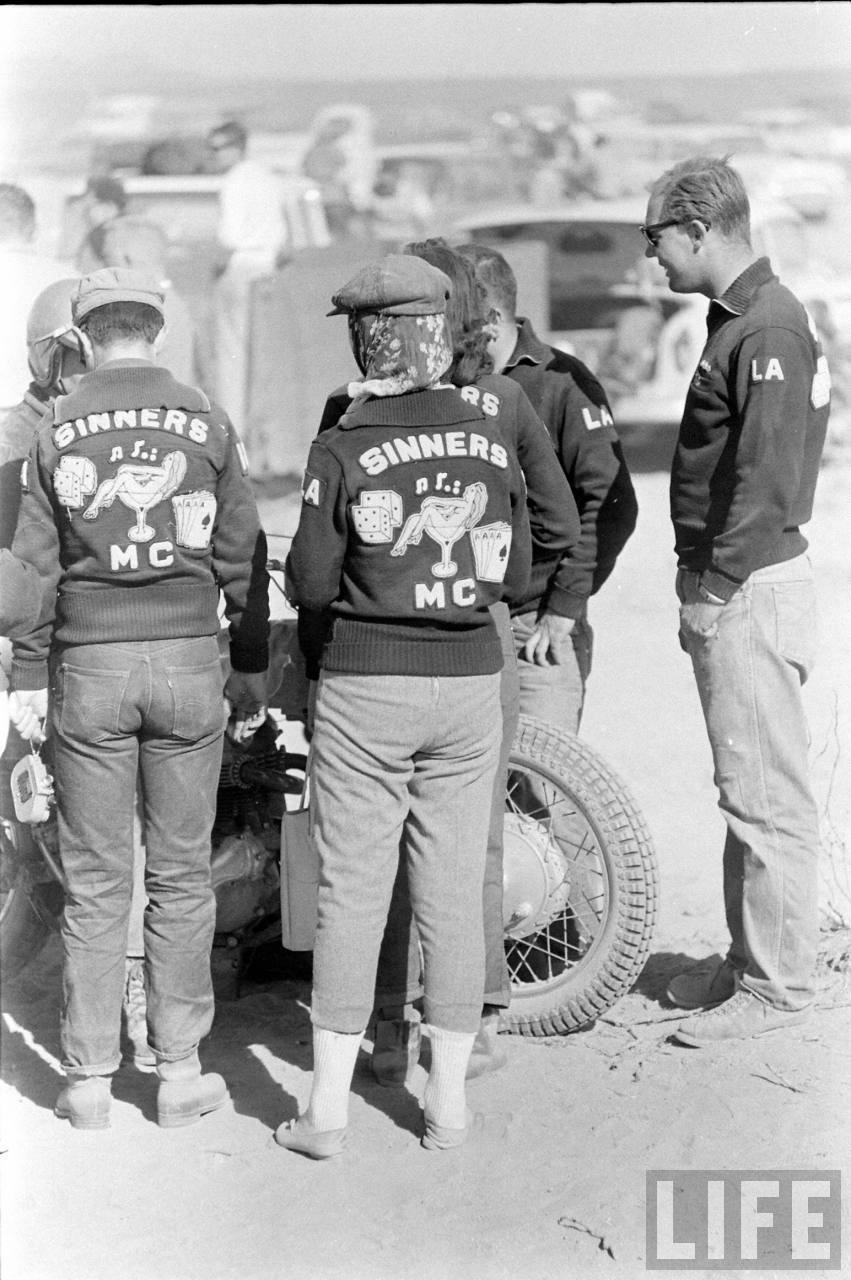

Take a look at the car club jackets above, for example. In the immediate post war years, young men and women wore these intricate, handmade jackets with chainstitching, embroideries, and patches on their backs and arms. An average patch might take about three or four hours to produce; the surrounding text maybe the same amount of time. The front was usually decorated with the member’s name and sometimes a title. Owners would proudly wear these, along with Levi’s 501s and clean white tees, when attending club meetings and social events. At one point, some American cities had hundreds of these clubs, with each one centered around a different type of car.

In his book Bowling Alone, Harvard professor Robert Putnam details the collapse of American community life. In one of his chapters, he goes through some of the statistics behind civic participation changes throughout the 20th century – everything from active organizational involvement to club meeting attendance. By any measure, things are the lowest they’ve been in decades. The average membership rate for thirty-two associations in 1997 was about half that of the 1960s, putting the ‘90s rates on par with those during the Great Depression.

To the degree that Americans still participate in civic life, they tend to be through big organizations – ones where they have to do little more than read monthly newsletters and donate money. Putnam writes:

Few ever attend any meetings of such organizations – many never have meetings at all – and most members are unlikely ever knowingly to encounter any other member. The bond between any two members of the National Wildlife Federation or the National Rifle Association is less like the bond between two members of a gardening club or prayer group and more like the bond between two Yankees fans on opposite coasts (or perhaps two devoted L.L. Bean catalog users): they share the same interests, but they are unaware of each other’s existence. Their ties are to common symbols, common leaders, and perhaps common ideals, but not to each other.

In that sense, the death of regional social clubs has also meant the death of the kind of clothing that came with their events. People still wear things to be part of social groups (at sporting events, most notably), but the idea of club clothing, as part of American life in any major way, feels alien. The concept of looking exactly like someone next to you, or at least wearing the same club jacket, almost seems like the sort of thing that could only be forced upon you at boarding school – a suppression of your individuality, rather than a way to feel connected to other people.

You can still find club clothing today on sites such as eBay and Etsy – old, discarded bowling shirts, sporting jackets, motorcycle jackets, etc. For the purposes of looking good as a non-member, retired varsity jackets and car club jackets probably make the most sense. Those will have been made the old-fashioned way, with chainstitching, handsewn embroidery, and handmade patches. Modern club jackets pale in comparison, partly because the designs are pushed out using automated and digital machines.

You can also check out Chain Gang, a small Los Angeles outfit that specializes in traditional chainstitching and handmade details, just as club clothing was produced in the mid-century. Some of their work today is for low rider car clubs, although much of what they do is for streetwear purposes (albeit in the old-school, social club aesthetic). You can catch them on Instagram (note some of the images there are slightly NSFW). Charlotte Willingale, who’s based in the UK, also chainstitches by hand (i.e. with nothing more than a needle and some thread). Her services might be good for a one-off project. I’ve been thinking about getting something inspired by the jacket below, which Jesse found on eBay. It was supposedly worn by a member of the Civilian Conservation Corps during the mid-1930s.

Lastly, for those interested in the death and revival of American community life, Bowling Alone is a great read. Putnam presents things in a way that’s both academically rigorous and easy-to-digest. It’s not about clothing per se, but rather social capital and alienation, which hits on topics that almost anyone will find interesting. You can pick it up for a few bucks through DealOz.