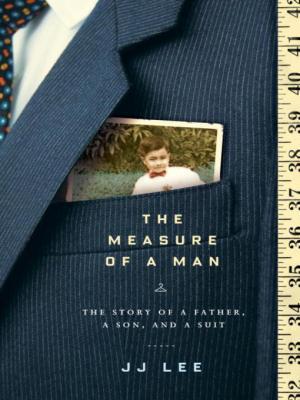

The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit presents us with an unusual form: the menswear memoir. It offers not the story of a life in the male garment trade, nor of a long career spent cutting and sewing. Nevertheless, it does contain a fair bit of material — pun only faintly intended — about developing a discerning sartorial eye, and about learning how to stitch a proper seam. Chinese-Canadian author JJ Lee made his name as a style writer and radio broadcaster, and only then, in his late thirties, did he begin studying at the feet of a master tailor. This in itself could make for a knocked-off entertainment freighted with a deadening subtitle like How a Mid-Life Apprenticeship Taught Me Everything I Needed to Know About Life, Love, and Lapels. But Lee elevates his work beyond such fluff by braiding in two other narratives: a history of the modern tailored suit, and the quick rise and prolonged, agonizing fall of his once well-turned out, aspirational, driven young father.

The Measure of a Man: The Story of a Father, a Son, and a Suit presents us with an unusual form: the menswear memoir. It offers not the story of a life in the male garment trade, nor of a long career spent cutting and sewing. Nevertheless, it does contain a fair bit of material — pun only faintly intended — about developing a discerning sartorial eye, and about learning how to stitch a proper seam. Chinese-Canadian author JJ Lee made his name as a style writer and radio broadcaster, and only then, in his late thirties, did he begin studying at the feet of a master tailor. This in itself could make for a knocked-off entertainment freighted with a deadening subtitle like How a Mid-Life Apprenticeship Taught Me Everything I Needed to Know About Life, Love, and Lapels. But Lee elevates his work beyond such fluff by braiding in two other narratives: a history of the modern tailored suit, and the quick rise and prolonged, agonizing fall of his once well-turned out, aspirational, driven young father.

I don’t emphasize Lee’s Canadianness trivially, and certainly not to trivialize his work. He every so often appears on CBC Radio, an institution that, as an internet listener south of the border, I’ve long admired. Citizens of smaller countries may not realize that living in the vast, liberty-obsessed United States also means living under the oppression of national media that, even in its public forms, strains constantly and desperately to impress 300 million people. The CBC, which doesn’t even seem to sweat appealing to all of its 33 million, therefore offers listeners a paradoxically greater freedom, at least from the very worst insults to their discernment. Maybe you can regularly hear as unadorned, information-rich, and audience-respectingly mild a broadcast as Lee’s radio documentary The Measure of a Man on the American airwaves, but I haven’t managed to. Have a listen, Put This On readers, and you’ll get a sense of where Lee comes from, not to mention where the suit itself comes from.

That broadcast expanded into this book. The project gains in the transition almost the entirety of Lee’s meditation on his relationship with his father, which meshes more closely with its historical and technical menswear content than you might expect. In writing about the source of a passion, we half the time end up writing about the men who sired us anyway (Pico Iyer’s father- and Graham Greene-centered The Man Within My Head being another strong recent example). Lee draws a line from his dad’s early nattiness, an advantage in the elder’s restaurant career, to his own nattiness, the sine qua non of the younger’s media career. Exactly how and where the father, a certain John Hing Foon Lee, cultivated his dress sense, the book leaves in obscurity, but his preternatural understanding of clothes making man gives us exciting reading as Lee père manages, seemingly by dint of style and self-possession alone, to gain a devoted wife, a lucrative position, and social juice all across Montreal before age 25.

“What does one need to live?” the eight-year-old Lee’s father asks him. “Food?” “You can spend $50 on food or $1,000. At the end of the month you will have nothing. If you spend $1,000 on how how you dress, if you look good, clean, and presentable, you will never go hungry. Someone will always give you a chance to work for them. Then you can eat.” But we have a hard time squaring these words of wisdom — words anybody reading this site accepts without hesitation — with Lee the elder’s subsequent, and thorough, self-destruction. The decline only comes through in fragments, but the closure of the restaurant he managed and a commensurate increase in his daily Scotch intake seems to send the man into a tailspin. In the process he loses his money, his career, his lady, his family, his hair, his furniture, and, in this book most tellingly, his taste in clothing. He also loses his life to a heart attack at age 52, leaving among his meager possessions only one garment of note: an awkward, corner-cuttingly Armani-inflected “blazer suit.”

This piece of late-eighties kitsch, albeit a deeply meaningful piece of late-eighties kitsch, becomes Lee’s project, his raison d’façonner. Less paunchy than his father in his final years, and also less broad-shouldered, he accrues just enough know-how to alter the suit for himself by apprenticing under Bill Wong of Vancouver’s Modernize Tailors. “My father’s suit,” Lee admits, “compared with the suits he owned in the past, doesn’t deserve the time I am going to put into it.” Yet even in this strange, bargain-rack mediocrity — “Bridge and Tunnel Tailors,” reads the label — John Hing Foon Lee must still have displayed more stylistic mastery than most men of his generation in North America. It’s not that the Baby Boomers can’t dress; it’s that, in the main, they don’t love to dress. Lee references Alan Flusser’s observation that, “in the 1960s and 1970s, fathers started dressing like their sons. As a result, two or three generations of men have lost the savoir-faire.” Had his father been totally rather than intermittently absent, the 1969-born Lee wouldn’t have it either.

Not that I wish I’d had Lee’s childhood, which he describes as materially precarious, emotionally unpredictable, and punctuated by savage parental conflicts. But he has got the savoir-faire, and The Measure of a Man showcases his inspiring drive to pursue ever greater understanding of clothing through nuts-and-bolts research and experience. And even he revels in the education of past fashion embarrassments, getting special mileage from a ghillie-collared gray number he wore to his father’s funeral. I struggle, though not as hard as Lee does, to directly infer meaningful lessons from the truncated life of this briefly suave, go-getting Chinese immigrant who suddenly lost his way. The author’s labors over the Bridge and Tunnel suit, let alone the book he got out of them, may strike some readers as a classic act of unwarranted East Asian filial piety. (Abusively drunken dads of other nationalities tend to get beaten up themselves, and even moms less brusque than Lee’s often find themselves ignored.) But he does vow, repeatedly, to treat his father as a negative example — to, at any cost, not become like him — and what sense he makes of their relationship comes only when he looks through the lens of clothes, style, and self-presentation. Perhaps you can relate.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy The Measure of a Man, you can find the best prices at DealOz.