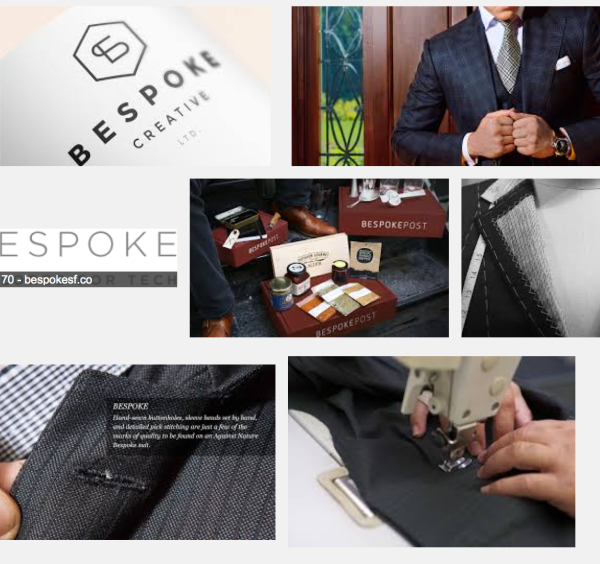

For The New York Times, Jim Farber explores the watering down of one of menswear’s favorite words:

For

much of the last century, bespoke referred almost exclusively to men’s

tailored suits, a practice idealized by the fine, and pricey, craftsmen

and women of Savile Row in London.The word itself, which dates from 1583, is a past participle of bespeak,

chiefly British, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and is

defined as “(of goods, especially clothing) made to order.”After

the Industrial Revolution, it became a descriptor of

specially commissioned products distinct from the mass-produced,

ready-made kind.Though

the term began in Britain, Americans have savored its snob appeal.

“Americans associate it with the British upper class,” said Deborah Tannen, a linguistics professor at Georgetown University.At

the same time, she said, the idea behind the word plays into something

deeply American: “Our individualism. We want everything made special for

us. Even when it comes to salad bars.”Also,

the word “sounds old-fashioned and traditional,” Ms. Tannen said,

naming two qualities common to the hipsterish faith that earlier

generations did things in a more natural, and so, more righteous, way.“It’s part of the authenticity hoax,” Mr. Riccio said.

With such a simple denotation, “bespoke” is a hard one to nail down even in its traditional confines. What’s bespoke and what’s made-to-measure? (I mean, we do have an answer for you.) But many businesses on the border between what’s traditionally known as made-to-measure and bespoke are happy to stretch it a little to exploit its snob appeal, and sometimes tailoring houses may arguably condescend a little to made-to-measure customers (“Simply put – if it’s not from Savile Row then it’s not real bespoke.”).

The bottom line is that these days pinning the word “bespoke” on a good means adding one thing for sure: cost. “Calling something bespoke automatically allows you to add $50 to the price.”