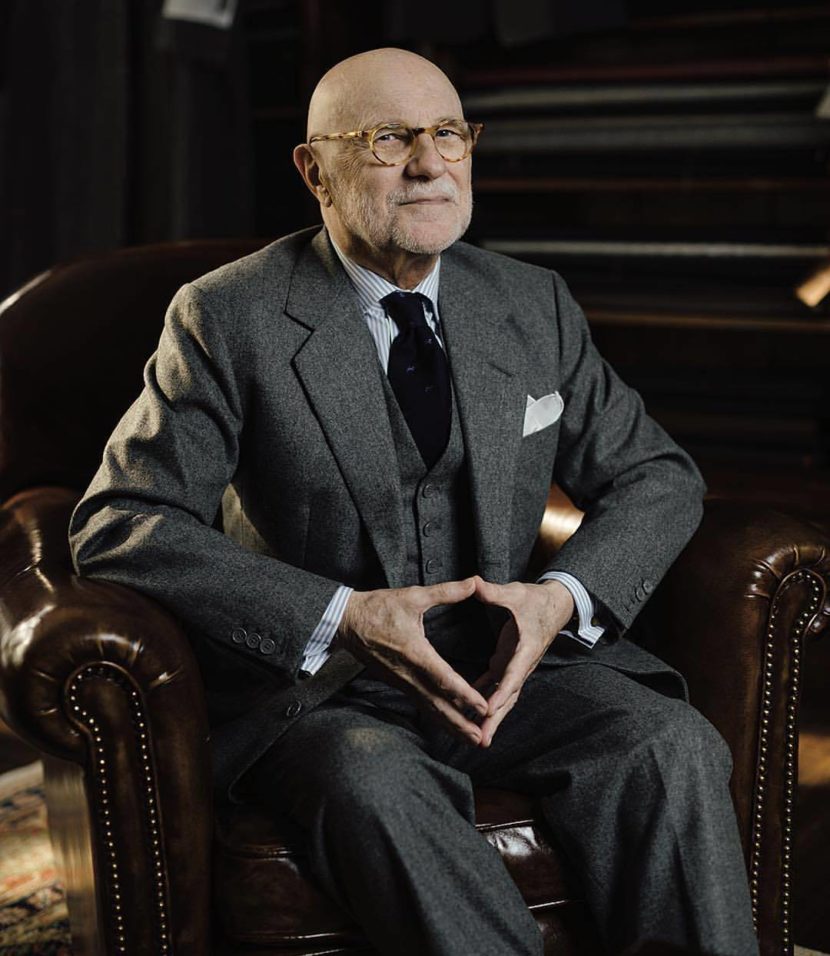

We’re big fans of Bruce Boyer. He’s one of the few style writers that connects clothes to culture, and can talk about classic men’s dress in a way that doesn’t feel pretentious. His writing often has a sprinkling of practical suggestions, which helps draw in people who are simply looking to dress better, as well as deeper dives into the semiotics of clothes. For people looking to just get into Bruce’s work, check out Eminently Suitable and Elegance — two books that were written decades ago, but remain great today, and mostly focus on tailoring. True Style, one of his newer releases, is a touch broader in terms of subject, but still focused on classic style. And Cigar Aficionado has an archive of articles Bruce wrote for them throughout the 1990s (a little known archive, but one of the best online collections of his work).

The Parisian Gentleman also recently published a post by Bruce on his life as a style writer. Like almost everything Bruce produces, it has a bit of interesting cultural history. An excerpt:

But with the end of WWII, and the energy of the postwar peace, this new group of designers (most of whom had cut their teeth in women’s wear) tentatively entered the menswear market and found some purchase, enough that a second generation began to emerge by the mid-’60s – some of whom had absolutely no connection to women’s wear, sometimes not even to design training – and by the early 70s there were both Ralph Lauren and Giorgio Armani, not to forget Alexander Julian, Geoffrey Beene, Perry Ellis, Stanley Blacker, Jeffrey Banks, Pietro Dimitri, Carlo Palazzi, Tommy Nutter, Michael Fish, and a growing number of even younger designers hot on their heels.

Clothing labels now began to make that telling switch from manufacturer’s names to designer’s names. THAT WAS A WATERSHED which indicated, as nothing else had, that the designer in menswear had arrived. Quickly designers began putting their names and logos on every form of product from the clothing to bed sheets and eye glass frames, cars, candy, and cans of paint. Perhaps they had reached some sort of endgame with Louis Vuition’s logo-imprinted condoms (for the man who really does have everything).

Lifestyle marketing was a watershed too. These designers brought the concept of lifestyle to the larger audience. “Lifestyle designing” at this point meant designing for people whose lives were thought to have no style.

In short, I came to writing about men’s clothing just shortly after the designers came to it. The ground floor of the building had just been laid. Lucky for me, I was in at the start of it all. And it was something of an international affair: there were designers from Great Britain via Savile Row and Carnaby Street, and from Rome and Milan, Paris and New York via the startling “New Wave” and “Neo-Realism” cinema which had emerged after WW II. The war had left a cultural vacuum, as well as the more obvious political and economic ones.

[…]

But a more important insight for me was my feeling that writing about men’s clothing had to be much different from writing about women’s clothing. I thought that it could be, it should be more serious, more meaningful. Writing about women’s clothing usually went something like this: burn your old wardrobe and get these new things so you’ll be thought both in style and youthful. Is it much different today? Fashion has a wonderful way of making us feel that, even if we don’t have the youth and beauty of runway models, even though we may be down, we’re not out. It keeps us in the game, and like religion, it offers hope and salvation.

My feeling was that men’s fashion writing should reflect, should be tied to something beyond itself, rather than this free-floating “fashion for fashion’s sake” sort of thing. Fashion writing should try to understand what clothing is about within a context, something in the tone of the age, the zeitgeist, something in the culture, something in both our emotional and intellectual life. As a philosophy student in college, I was always opposed to the idea that any aspect of human endeavor occurs in a vacuum, isolated from other aspects of life. In that sense, I suppose I’ve a holistic philosophy. This idea of “art for art’s sake” never appealed or even made any sense to me. What the hell is the sake of art anyway? It was all too rarefied, ethereal, and segregated for me.

I wanted to tie fashion and our concerns about clothing to other aspects of culture to make it more real and relevant, to integrate it into our cultural and intellectual outlook somehow: I wanted to tie it to sociology, or history, or psychology, or literature, politics, or biography. To something, so that it wouldn’t exist in this artificially imposed isolation understood only by the acolytes, this vacuum of magical aesthetic navel gazing. I was not writing for dandies, but for the man who simply wanted to be more aware and in control of his appearance. I wanted to make writing about clothing readable and approachable for men who were not necessarily interested in fashion, but were particularly interested in dressing well and understanding its importance. And for those who found clothing a joy in their lives.

You can read the rest at The Parisian Gentleman.