Most Americans I know hesitate to embrace all of “American culture.” This makes sense, considering the broadness of any such umbrella, one that would have to cover a population of 300 million with origins across the entire world. So we pick and choose from this country’s bulging social, political, cultural, and aesthetic grab bag, taking what we want and leaving (when not insistently repudiating) the rest. You might follow baseball but dismiss football, dream of your own car but not your own house, or hold one opinion about country music and its polar opposite about rap. This goes as well for the clothing styles we think of as distinctively American. To divide us, just start a debate about the influence of athletic wear on our national dress. The clothes of surfing, skating, and tennis, among other sports, have all since the Second World War greatly influenced everyday wear here — not, I would think, to the approval of every Put This On reader.

Most Americans I know hesitate to embrace all of “American culture.” This makes sense, considering the broadness of any such umbrella, one that would have to cover a population of 300 million with origins across the entire world. So we pick and choose from this country’s bulging social, political, cultural, and aesthetic grab bag, taking what we want and leaving (when not insistently repudiating) the rest. You might follow baseball but dismiss football, dream of your own car but not your own house, or hold one opinion about country music and its polar opposite about rap. This goes as well for the clothing styles we think of as distinctively American. To divide us, just start a debate about the influence of athletic wear on our national dress. The clothes of surfing, skating, and tennis, among other sports, have all since the Second World War greatly influenced everyday wear here — not, I would think, to the approval of every Put This On reader.

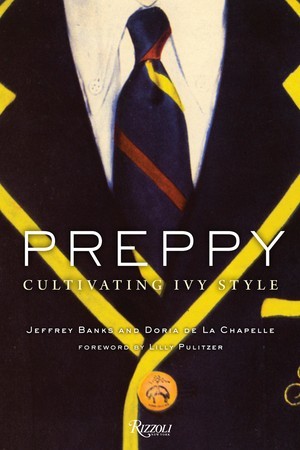

For a richer object of study, consider preppy, as Jeffrey Banks and Doria de la Chapelle do in Preppy: Cultivating Ivy Style, which examines the eponymous style of dress from its origins in the twenties through its adaptive evolution in each subsequent era. But how to define it without pinning it down too squarely? The authors quote Dierdre Clemente in the Journal of American Culture as astutely calling it an “ironic blend of rumpled and conservative.” Preppy, at its most viable, strikes me a rakish hybrid of the primly traditional and insouciantly athletic. This sounds like the stuff of mere trend, but the book marshals a quote on the contrary from social critic John Sedgwick arguing that “fashion has no place in the Ivy League wardrobe. The Ivy Leaguer is really buying an ethic in his clothing choices [ …] a puritanical anti-fashion conviction that classic garments should continue in the contemporary wardrobe like a college’s well-established and unquestioned curriculum.” The doctrinaire preppy wears the correct navy blazer and khakis, naturally, but only when correctly weatherbeaten.

We’ve brought up two distinct but related American social settings: the Ivy League, as in the league of eight historically prestigious East Coast colleges, and prep schools, as in the college preparatory schools evoked by the term “preppy.” That latter concept has lost some meaning now that America tries to ram as many students through four-year universities as possible. But when we talk about classic prep schools, we talk about prep schools as regarded in the twenties up through the mid-sixties: northeastern academies, mostly private, frequently boarding, usually stylistically rigid, and always geared toward feeding the Ivy League. “I want to go somewhere where people aren’t barred because of the color of your necktie or the roll of your coat,” moans Tom D’Invilliers in the thoroughly prep-schooled F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise. Banks and de la Chapelle use the line to underscore the conservative roots of preppy style, although I like to think their inclusion of not one but two photographs of William F. Buckley, Jr. speak even louder. One picture finds him on a horse; the other, on a yacht.

Despite its roots in stylistic conservatism, preppy style no longer signals particularly strong political conservatism. Preppy presents us with a full-page 1980 photo of the ideologically nebulous George H.W. Bush, then in his days as vice-presidential candidate, cutting an uncharacteristically rugged, relaxed figure on the porch in Kennebunkport. And no catalog of the icons of preppy can do without an appearance by liberal Democrat John F. Kennedy, especially in white shirt, repp tie, and grey flannels. Preppy devotees still look to images of Kennedy as theologians scrutinize ancient scripture; the men I see profiled in the traditional Americana-focused Japanese magazine Free & Easy magazine tend to display J.F.K. memorabilia prominently in their studies, offices, and dens. The prep school and Harvard Law-educated Barack Obama doesn’t make it into the book, though his wife and daughters do, but those who find preppy style unacceptably Establishment-tinged might advise Obama himself, representative of an unprecedentedly diverse United States of America, to steer clear of it.

I couldn’t personally endorse that recommendation, especially when looking at the book’s glorious two-page photograph, staged by Joshua Kissi and Travis Crumbs of Street Etiquette, of eighteen black takes on Ivy League dress. These reinterpretations of preppy, though at no point especially flamboyant, remind me how much potential is has in reserve for life beyond the Buckleys, the Bushes, and the Kennedys. “What started out as an exclusive, white-Protestant, male, clubby way of dressing for the Elite Few,” as the authors put it, “has morphed into an inclusive, multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-religious, pan-gender, meritocratic way of dressing for the Elite New.” We saw the roots of this in Take Ivy, Teruyoshi Yoshida and company’s 1965 study of Ivy League aesthetics, and at this point certain signs, like the 1986 purchase of unbending Yale clothier (and G.H.W. Bush brand of choice) J. Press’ by Onward Kashiyama, suggest that the pursuit of preppy outside America has outpaced the homegrown variety.

Preppy itself uses shots of the style as practiced in Japan, as well as in Korea, birthplace of my girlfriend, a lady who uses the elements of Ivy in more interesting ways than any clubby white male of my acquaintance. (I do admit to a bias here, and direct anyone interested a more objective viewpoint on preppy women’s wear to Banks and de la Chapelle’s chapter on the subject.) It seems the preppy-wearers to watch today, whatever their national origins, would never have made it into the club in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s day, or even in J. Fitzgerald Kennedy’s. This goes just as much for me, despite looking as pale and stern as a J.C. Leyendecker illustration, as it does for any of the aforementioned Elite New; growing up on the West Coast, I didn’t even know what a prep school was until my mid-twenties. We employ the preppy style now not as a symbol of belonging, but of not caring whether we belong, and thus we wear it with more freedom. It reminds me of my favorite thing about this country, where “freedom” runs the constant risk of turning into a buzzword: not the pride of adhering to its traditions, but of bending them to each of our own wills.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy Preppy, you can find the best prices at DealOz.