I relish the menswear enthusiast’s life for a number of reasons, the first and foremost being that we get less homework than women’s wear enthusiasts do. This very idea may strike you as ridiculous, especially if you keep up with Put This On and countless other sites like it, but remember: they strive, often frantically, to keep up with an ever expanding breadth of garments, accessories, lines, and designers. One lady’s wardrobe may well include dozens, or even hundreds, of each. The menswear enthusiast plunges into something much narrower and deeper. We go down, you might say, a historical hole, digging our way toward the origins of the fifteen or twenty items we wear with the utmost regularity. Chinos, tweed jackets, button-down shirts, aviator sunglasses, Chuck Taylors: the versions we own today have undergone minor changes since the models’ invention, whereas women’s clothing, by comparison, endures regular and thoroughgoing revolutions. But boy, how much you can learn about those minor changes, let alone about the inventions themselves. “A minute to learn… a lifetime to master,” went the old Othello slogan, and the same applies to the game of men’s dress.

I relish the menswear enthusiast’s life for a number of reasons, the first and foremost being that we get less homework than women’s wear enthusiasts do. This very idea may strike you as ridiculous, especially if you keep up with Put This On and countless other sites like it, but remember: they strive, often frantically, to keep up with an ever expanding breadth of garments, accessories, lines, and designers. One lady’s wardrobe may well include dozens, or even hundreds, of each. The menswear enthusiast plunges into something much narrower and deeper. We go down, you might say, a historical hole, digging our way toward the origins of the fifteen or twenty items we wear with the utmost regularity. Chinos, tweed jackets, button-down shirts, aviator sunglasses, Chuck Taylors: the versions we own today have undergone minor changes since the models’ invention, whereas women’s clothing, by comparison, endures regular and thoroughgoing revolutions. But boy, how much you can learn about those minor changes, let alone about the inventions themselves. “A minute to learn… a lifetime to master,” went the old Othello slogan, and the same applies to the game of men’s dress.

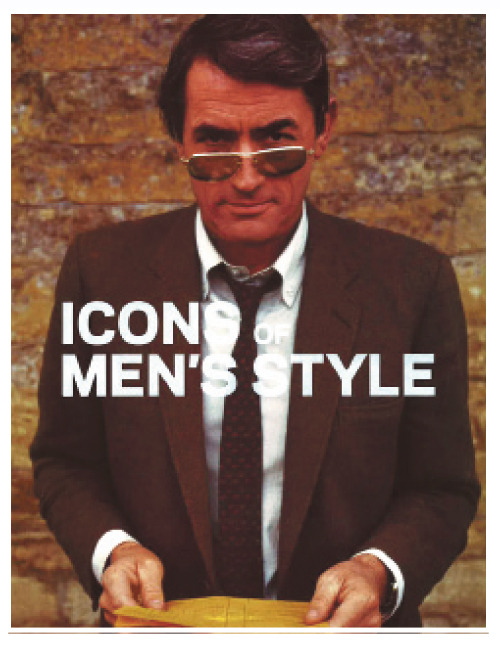

Much of our early menswear education comes from popular culture, often in minute-long flashes. Josh Sims’ Icons of Men’s Style takes some time, if not a lifetime, to offer a bit more mastery on 52 particularly timeless, universally recognized items, most of which got their break from twentieth-century American popular culture. Gregory Peck appears on the cover wearing aviators; Tom Cruise, encased in Top Gun gear, occupies a full page doing the same. An image of Jimmy Stewart dominates the chapter on tweed, as one of Ronald Reagan dominates the chapter on the sweatshirt. A shot of Michael Jackson shooting Thriller illustrates the wearing of loafers. The text cites Steve McQueen nine times, four of them with pictures. Magnum P.I., you’ll feel relieved to hear, makes an appearance as well. Sims writes up a scattering of items now rarely seen in the United States — the Barbour jacket, the Breton top — but tends to stick with what we’ve seen on the bodies and in the hands of American film stars, musicians, athletes, and politicians. Yet given the considerable influence of midcentury Americana on the rest of the world, a certain internationalism remains.

Should Sims have titled his book more precisely? Not if you account for the publishing industry’s addiction to the sound of the definitive, and for the striking endurance of the elements of men’s style popularized in America forty, sixty, eighty years ago. A name like Icons of Mid-Twentieth Century American Men’s Style says little, in this light, that Icons of Men’s Style doesn’t. But the London-based author doesn’t fail to give his own land its due. “Perhaps simply because of the mysterious, fate-like process that culminates in ‘cool,’” he writes in the introduction, “it was the items in this book that captured the imagination.” The periodic bursts of British influence felt across the twentieth century appear here in articles like the polo shirt as worn by Paul Weller, and the German-conceived Doc Martens as worn by “punks goths, grungies, hard mods, and, most notably, skinheads.” A mid-seventies Mick Jagger models a perhaps unexpected inclusion, the Panama hat; that era’s David Bowie, the lonely alien of The Man Who Fell To Earth, does the same for the particularly non-American duffle coat. Sean Connery’s James Bond looms over the chapter on the dinner suit, an inclusion so obvious that my eyes passed over him on the first few trips through the book. Only the final page, on the necktie, delivers the Duke of Windsor; without him, can a menswear book really qualify for the category?

But these litanies of famous names and well-known items make the project seem more comprehensive than it is, or intends to be. Sims has, no doubt, produced an odd beast: neither purely instructional nor purely referential, too deliberately written for a photo book but too richly visual for a straight-on text. It delivers perhaps too much information for the menswear neophyte while not quite enough for those of us who thirst for design and historical detail. Well-meaning relatives will no doubt hand many of us copies as Christmas presents, and they won’t have made an entirely inappropriate choice. As hard a time as I have pinning down what I’ve learned from the book, I also know that it hasn’t taught me nothing (a common enough practice in menswear writing), nor has it misled me (an even clearer and more present danger). It has, shall we say, reminded me: reminded me of the menswear stalwarts I’ve yet failed to add to my wardrobe, reminded me of how those I do own have been best and most prominently worn (the way Steve McQueen wore them, in most cases), and reminded me to think clearly about the fascinating process of how, exactly, something ascends into what Sims calls “menswear canon.”

Also neither fish nor fowl when it comes to formality, Icons of Men’s Style places the dinner suit and the sweatshirt fewer pages apart than you’d think. Page 177 displays no fewer than thirty Rolex watches; on page 178 appear nine humble, weathered, decal-emblazoned Zippo lighters. Sims briskly explains the details of the Zippo’s stealthy but nonetheless impressive design evolution just as he does the (on reflection) almost garishly overt engineering and branding of the Montblanc Meisterstück. He’d have us to turn the same interested eye toward one of Tom Selleck’s shirts from Hawaii as we would one straight off Jermyn Street. Agnostic toward refinement, he reflects both the best and worst about the liberating American influence on men’s style. We’ve all felt this liberation when mixing a tailored blazer, say, with a polo shirt, work boots, and worn khakis whose pocket contains a Dunhill Rollagas, to assemble from the book’s collection what today seems a relatively tame combination. Such freedom of dress brings great potential for victory — and for that mysterious “cool” — but much greater potential for defeat. Hence the need to periodically, indeed rigorously, ground oneself by checking in with the most enduring garments, objects, design elements, and actual men. In other words, with the icons.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy Icons of Men’s Style, you can find the best prices at DealOz.