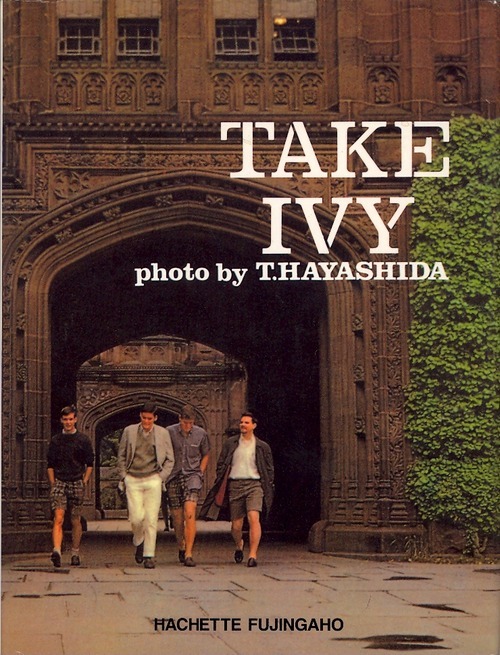

Boy, I want to go to college. Alas, I’ve already gone, and even if I hadn’t, being that I’m nearing thirty years old, “leading a college life in one’s thirties would be way too late.” That observation comes from a no less authoritative a study of university life and style than Take Ivy, but still, we must make certain allowances for temporal and cultural distance. First, the book deals exclusively with life and style at the “Ivy League” schools of America’s East Coast. Second, it originally came out in 1965. Third, the men who wrote it, Teruyoshi Hayashida, Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, and Hajime “Paul” Hasegawa, all come from Japan. These may seem like considerable stumbling blocks for many in the market for this sort of book — I myself actually have more experience with Japan than with anything on the East Coast, let alone with the year 1965 — but the final product nonetheless raises a burning desire within me to grab my penny loafers, lacrosse stick, and sweatshirt emblazoned with my graduation year and confab with my chums on the quad.

Boy, I want to go to college. Alas, I’ve already gone, and even if I hadn’t, being that I’m nearing thirty years old, “leading a college life in one’s thirties would be way too late.” That observation comes from a no less authoritative a study of university life and style than Take Ivy, but still, we must make certain allowances for temporal and cultural distance. First, the book deals exclusively with life and style at the “Ivy League” schools of America’s East Coast. Second, it originally came out in 1965. Third, the men who wrote it, Teruyoshi Hayashida, Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, and Hajime “Paul” Hasegawa, all come from Japan. These may seem like considerable stumbling blocks for many in the market for this sort of book — I myself actually have more experience with Japan than with anything on the East Coast, let alone with the year 1965 — but the final product nonetheless raises a burning desire within me to grab my penny loafers, lacrosse stick, and sweatshirt emblazoned with my graduation year and confab with my chums on the quad.

“I spent my high school years picturing myself on the campus of an Ivy League university, where my wealthy roommate Colgate would leave me notes reading, ‘Meet me on the quad at five,’” wrote David Sedaris. “I wasn’t sure what a quad was, but I knew that I wanted one desperately.” The quartet of trad enthusiasts who put together Take Ivy presumably felt a similar, if better-informed, quad-related longing. When my time came to file college applications, I couldn’t have told you which schools made up the Ivy league beyond Harvard and Yale, and anyway, articles had reported for years that undergraduate education at those two wasn’t what it used to be. Having grown up on the West Coast cultivating a fear of what I assumed to be the Ivy League’s formidable wealth, daunting application standards, and harsh social judgment, I swallowed that line whole. While Take Ivy’s candid, idyllic shots of the then-distinctively garbed students of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Pennsylvania, Columbia, Dartmouth, Brown, and Cornell don’t make me wish I had applied to those schools back in 2002, they do make me wish I had applied to those schools back in 1965.

We should feel grateful that this project, tasked with documenting that time and place, is a Japanese one. Working toward a definition of the style it simply labels “Ivy,” the book announces an expectation: “In order to entirely understand the spirit of ‘Ivy,’ you must appreciate and master all aspects of American East Coast culture.” So dictate the rigors of Japanese enthusiasm. To go by its major cities filled with thousands of tiny bars, eateries, and bookshops, each fixedly devoted to the reproduction and perfection of a single aesthetic, Japan displays an unparalleled capacity for appreciation and mastery. And though eighteen-year-old me had wishfully written off the Ivy League as a superficial choice, a pricey shell of its former self, Japanese enthusiasts better understand the importance — possibly the all-importance — of surface. “Appearances are reality,” Donald Richie wrote of Japan in his classic travelogue The Inland Sea. “The mask is literally the face, and the cynic can find no telltale gap because none exists. [ … ] Reality is only skin deep because there is only skin. The ostensible is the truth.” Or as a longtime British expat there told me, “You want to know who the artists are here? The ones wearing berets.” It only sounded like a joke.

If you want to know who the Ivy Leaguers are, according to Take Ivy, they’re the ones clad in school colors and varsity jackets, lovingly polishing their VW Beetles and vintage Packards, listening intently to their folk and jazz albums (the title puns on the Japanese pronunciation of Dave Brubeck’s hit, “Teiku Faibu”), and cramming desperately in hundred-year-old libraries. They look and play most completely — they fully assume and internalize the role of — the well-born East Coast college student. “Though I will leave it up to historians to evaluate his accomplishments to mankind,” one of the authors writes of Harvard man John F. Kennedy, ”I take this opportunity to stress that he certainly lived the ideal life of an Ivy Leaguer.” But no image of J.F.K., on campus or off, appears in these pages. Photographer Teruyoshi Hayashida captures only anonymous, unaware Ivy leaguers, though ones ostensibly possessed of an exemplary look and bearing. Readers used to Western men’s style coverage might see in these pictures sartorial self-expression, youthful personalities in a highly romanticized setting outwardly manifesting themselves as Ivy dress. But it makes for a worthwhile exercise to, at the same time, consider Take Ivy’s assumption that style choices make the being as much or more than the being makes the style choices.

Put This On readers may mostly concern themselves, despite the authors’ warning not to, with these students’ clothing. Beyond the strange prevalence of white sweatsock, often exposed between madras short and dark loafer, you could now wear much of what Take Ivy documents onto a college campus, if not every day, without raising an eyebrow. Surely this has something to do with college campuses, at least across most of America, having since become stylistic free-for-alls where few choices could raise eyebrows, and indeed, unbending adherence to the Ivy wardrobe might mark out a modern student as eccentric. But from this vantage, we see that the 1965 Ivy leaguer’s crisply causal way with chinos, button-downs, and branded university merchandise has become timeless and even placeless enough to disperse through the rest of society. Anyone can wear Ivy now. This counterbalances the studied blandness some may come away from this book feeling afflicts the style, due in part to the wearers’ deadening, if expected, lack of diversity. Take Ivy sees, with only rare exceptions, a white world, pale even by that standard. Countless ethnic studies theses will surely be written on the fraught dynamic between this white-bread crowd and the fervently admiring Japanese gaze.

But most of the text simply reads, in the current decade and the first to see Take Ivy published in English translation, as a touching elegy for a subculture now seemingly hollowed out. “We envy them,” the authors write of their Ivy Leaguers, “for they are tackling their college experience, one of the most precious and glorious times of their lives, with youth and energy.” Every soon-to-be undergraduate today hears the same about what awaits them, but those pronouncements ring piously where Hayashida, Ishizu, Kurosu, and Hasegawa’s words exude an almost embarrassing sincerity. Having washed up myself on the campus of UC Santa Barbara aghast at the saturation of pajama pants and flip flops — and those just on the ladies — I can’t help reading the carefully insouciant styles examined here as emblematizing the last era when, built upon false verities and unearned privilege though it may have been, an American college education could not be taken lightly, when even gentleman’s Cs, afternoon drinking, and casual dress demanded a kind of mastery. The Ivy League’s heyday has gone, but its styles remain surprisingly viable today. Whatever our station in life, we fail to incorporate them into our 21st-century wardrobes at our peril, and we’ll find no more earnest or evocative primer for the task than Take Ivy.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy Take Ivy, you can find the best prices at DealOz.