We don’t write much about designer clothing, but this season’s Dries van Noten collection is pretty great. For this year’s fall/ winter line, the Belgian designer licensed some old, archival labels from some of Britain’s most storied mills. Names that include Lovat Mills from the Scottish borders town of Hawick, makers of some of the finest and spongiest tweeds. And Fox Brothers, inventors of woolen flannel, who today sell some of the best mottled and warm flannel.

The labels were used for a small collection of this season’s DvN totes, t-shirts, and sweaters. Supposedly, when the designer approached the mills, they were confused. Back in the day, before the advent of ready-to-wear, mills included these labels along with their cloth, which they shipped out to custom tailors. Those tailors would then, on request, sew the label on the interior of a jacket, so a client would remember the provenance of the fabric (something still practiced today for those who commission bespoke clothes). These labels were always meant to be used on the inside of garments – tucked away, hidden, and unseen – not shown to the world. Supposedly the mills didn’t understand the concept at first, but they were happy to license their labels anyway.

The collection came out pretty great, and even the most uptight of traditionalists probably can’t help but be charmed. I particularly like the wool tote and t-shirt that feature Fox Brothers’ label, as well as the cream colored Shetland with Jaimeson & Smith’s name. You can find the collection at Barney’s, Mr. Porter, and Selfridges. (Beware, prices are high, but that’s designer fashion).

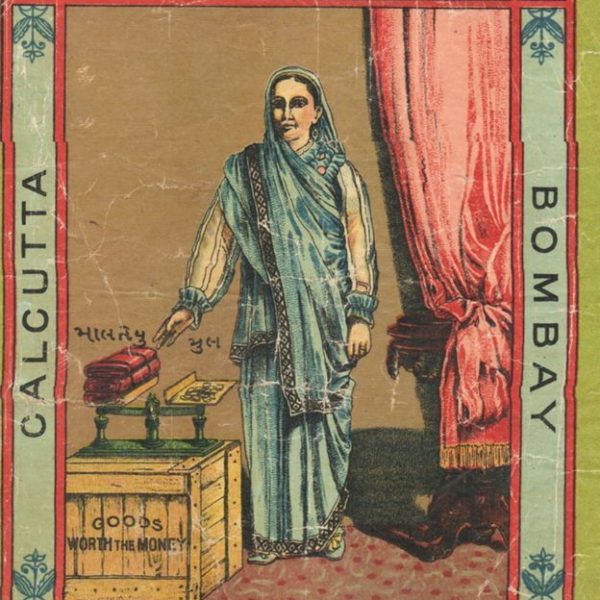

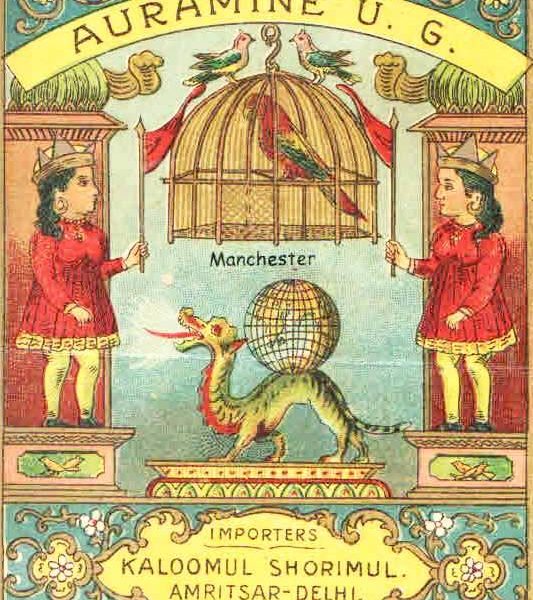

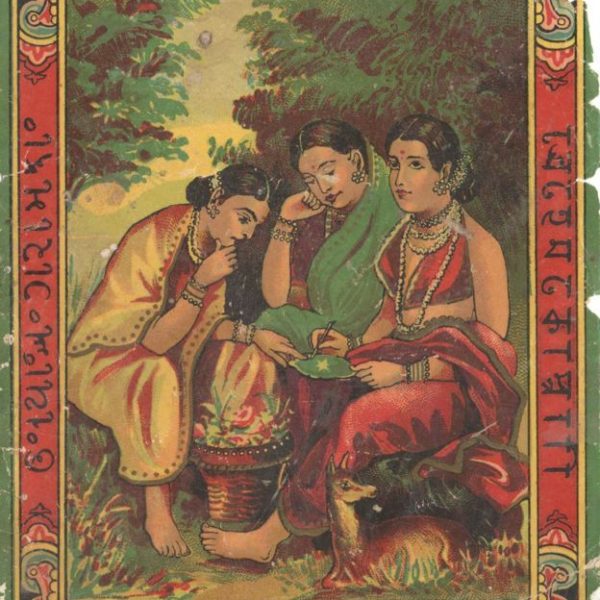

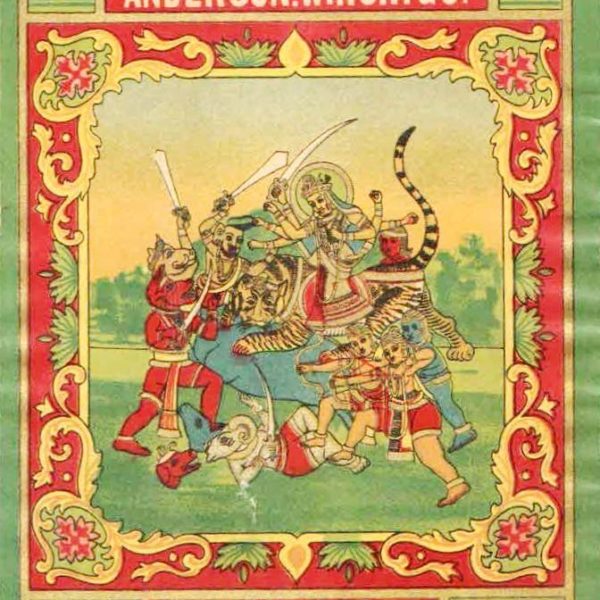

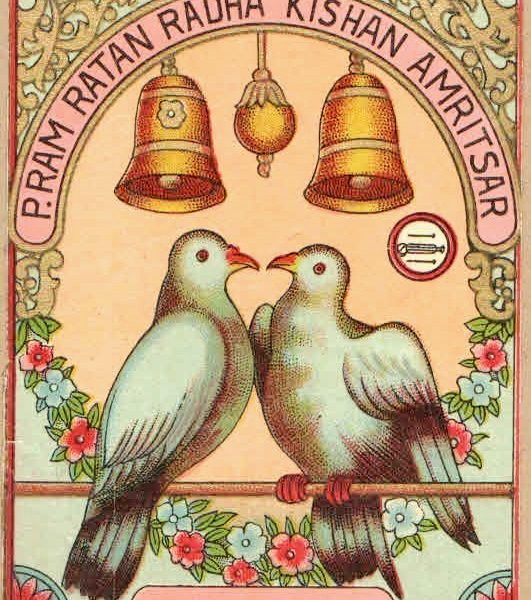

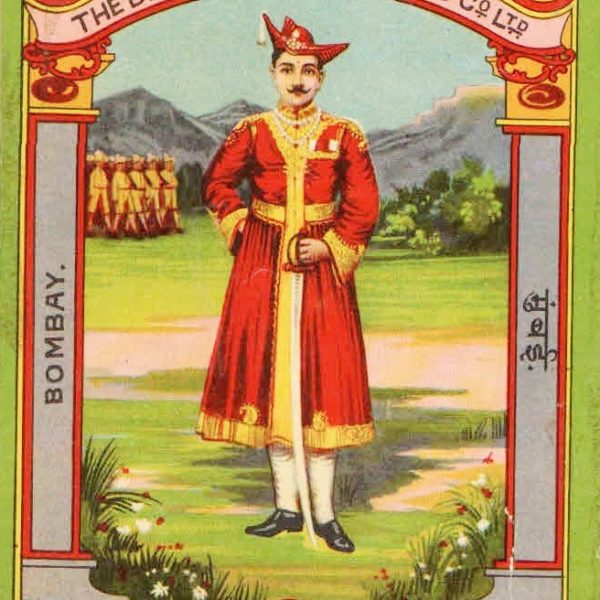

The collection reminded me of something else about British history. About a hundred years ago, British mills used to print little paper strips, known as “shipper’s labels,” which you can see at the top of this post. These were included with bolts of cloth, woven in Britain but destined for India.

This was back when India was still under British colonial rule. From about the 16th to 18th century, India had a leading industry in finished cotton fabric production – they both grew the cotton fibers and wove it into fine materials. Once the British came, however, the country went through a deskilling, moving from a full up-and-down producer to just a supplier of raw cotton. This was a result of a forced and imbalanced trade policy. Britain put up tariffs against Indian imports in order to protect their own industries, but at the same time, forced India to accept British goods. As a result, trade flowed in two distinct ways. Raw cotton went from India to Britain, since it was cheaper to grow cotton in South Asia, then finished cotton fabric moved from Britain to India.

Since the British needed to market their goods, they printed up these little tickets to help make their Western fabrics seem more appealing. The ticket designs were based on British conceptions of Indians, with whom producers had little direct contact, so they featured popular (and at times clichéd) depictions of the Indian people, lifestyles, places, mythologies, and deities. Sometimes, at the bottom of the ticket, the mill would print where the fabric was originally woven. A few of the examples above show the cities Glasgow and Manchester.

Some of these tickets ended up becoming quite popular in India. Collectors valued them for their artistic appeal; devout Hindus used ones with religious iconography in their prayer rituals. You can still find some of these labels floating around on eBay. Just search for phrases such as “India cloth label,” as many people don’t know these originated in Britain.

Of course, today, these labels are no longer used in the textile trade. The British textile industry still has a close relationship with India – many respected names in the business actually weave their cloth now in South Asia – but none, as far as I know, use these colonial style tickets.

The one thing that’s still produced from that era is Khadi, which is a type of handwoven cotton fabric that became an important symbol to the Indian independent movement. When Gandhi launched the Swadeshi movement in 1918, he called on Indians to boycott British imports and weave their own fabrics at home. And today, you can still find handwoven Khadi in India. I have an indigo-dyed Khadi dressing gown that I like to wear in the spring and summer months. As with many fabrics that come out of that country, it’s terrific at dealing with the heat.