In the 18th century, Russian leather was widely considered to be the finest in the world. It was known for being incredibly rich in color, supple, and water resistant. There was also something about its aroma that allowed it to repel insects. It was truly unique.

Tanneries in Western Europe tried to duplicate Russia’s distinctive, beautiful, and hardwearing leather. They even sent spies to try to uncover trade secrets. Unfortunately, very little became known. What they did find out, however, was that the pre-tanning stages alone took up to six months. During the tanning stage, the hides, soaking in previously-used tanning fluid, were more or less continuously turned by hand for about four months. Then they were transferred to pits where they soaked in water mixed with bark from willows, poplar, oak, and larch trees for about eighteen months. After that, they were cured, dried, beaten with mallets, pared with shaving knives, and then pulled over sharp-edged rings, which cut them with the fine cross-hatched scores they were known for.

Though the process was vaguely known, Western tanneries couldn’t reproduce it because they could never identify the formula for the mysterious dressing oils. By the time the Russian Revolution came in 1917, the new provisional government shut production down, and secrets of how it was made became lost for good.

Then, in 1973, a team of British deep-sea divers was exploring the waters of Plymouth Sound, where they found the broken timbers of a sunken ship. The ship’s bell identified it to be the Metta Catharina, a 100-ton Baltic ship that set sail from St. Petersburg and for Genoa in December 1786. She never made it, however, as she was sunk during a storm.

Littered around the seabed of the broken ship, the divers found bundles and bundles of hides. They brought the bundles up to surface, and when they untied them, the packages opened up like packs of vacuum-sealed coffee. Apparently, the hides’ immersion in black mud, combined with their mysterious oils, allowed them to go nearly 200 years with very little water penetrating.

At first, the divers didn’t even know what they found. They went to a bar the next night and casually talked about it. A young leather worker, Robin Snelson, overheard and asked if he could see the hides. They agreed.

Snelson developed a cleaning technique to help restore the hides to their original quality. Once cleaned, they beamed with rich colors, varying from deep claret to lighter sienna. They also revealed their cross-hatched surface, and began giving away their distinct sweet aroma. There was no other leather with this aroma, and it was clear these were the famed Russian leathers that was once only a historical legend.

Word spread, and in 1986, two bespoke shoemakers from Cleverly approached Snelson about using the hides for their shoes. Cleaverly is widely regarded as one of the best bespoke shoe making houses in the world, and everyone agreed that only they would do the hides justice.

I’m unsure how many shoes were made from the hides, but I think it was something around 200. Ready to wear pairs were sold for around $2,000, while bespoke pairs were around $5,000. The client list is private, but its been revealed that the first pair was made for Prince Charles.

Nobody knows how many hides are left buried in that wreck. Recovery has not been easy, and the job is incredibly dangerous. The bundles near the bows and stern have been cleared out, for the most part, but some believe there may be more in some of the unexplored areas. However, those areas are too dangerous to approach, and nobody has been willing to risk their lives for the additional hides. For now, it seems like the quantity above shore is all that there is.

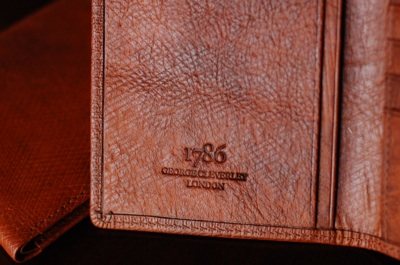

The shoes have all been sold off by now, but some companies have enough scraps to make a few small accessories. For example, this company still makes wallets out of the 225 year-old Russian leather. The prices are expensive, but that’s the cost of owning a little bit of legendary menswear history.