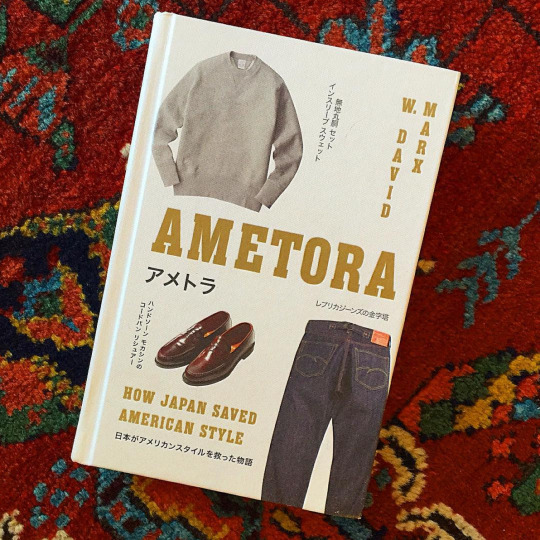

Whether you’re into prep, denim, or streetwear, W. David Marx’s new book Ametora will have something to say about why you wear the things you do today. Ametora (which is Japanese for “American traditional”) traces Japan’s obsession with American style, going all the way from the days of Ivy Style and Take Ivy to Heavy Duty, vintage workwear/ denim, and then street fashion brands such as A Bathing Ape. And, of course, how those Japanese trends eventually influenced the heritage revival in the US and our own tastes. His book is a fascinating look not only into men’s style, but also cultural identity and globalization. We recently chatted with Marx about his project.

What do you mean when you say Japan “saved American style?”

Saved here has a few meanings. First, there’s saving as in archiving. The Japanese fashion industry has done an incredible job archiving the entirety of American style over the last seventy years — from Ivy to workwear to outdoor to rock’n’roll greasers to military. If the United States disappeared tomorrow, we could easily reconstruct the history of American style just from Japanese sources.

Then there’s the more debatable meaning: saving as rescuing. There are very concrete examples of where Japan has resuscitated extinct or nearly extinct parts of the American clothing tradition. The most obvious is selvedge denim. Just as American mills stopped weaving denim on narrow shuttle looms in the early 1980s, Japanese brands Big John and Studio D’Artisan pushed their local denim suppliers to make slubby selvedge.

And there is an economic argument: Japanese consumption of traditional heritage American brands such as Alden (or even streetwear brands such as Stussy) gave those companies financial stability when American tastes would have otherwise led them elsewhere.

We shouldn’t forget how bleak everything looked for traditional styles in the U.S. about a decade ago. That’s not true in Japan, however. In 2005, more people in Japan dressed like 1960s Harvard undergraduates than actual Harvard undergraduates. So we should at least explore how much of today’s U.S. heritage revival is influenced by the Japanese archived version rather than being an organic flow from the actual historical tradition. Americans have gone back, intentionally or not, to Japanese examples of American style for reference because they were often more available than the original garments.

You have a ton of primary sources in this book, much of which has never been seen before. Tell me a little about what it took to research this topic.

Back in 2000-2001, I wrote my college thesis on A Bathing Ape and Japanese streetwear, so I’ve been interested in the history of Japanese fashion since then. For Ametora, I started reading and researching in earnest about five years ago when I met VAN Jacket founder Kensuke Ishizu’s son Shōsuke and realized I should talk to everyone involved with bringing American fashion to Japan.

Besides interviews, the other important resource included old Japanese magazines, especially Men’s Club, Heibon Punch, and Popeye. I spent a lot of Saturdays in Tokyo’s National Diet Library photocopying magazine articles and obscure out-of-print books. Magazines used to have a lot of group discussions, which made it easy to understand how everyone felt about style in each era.

The only part of Ametora not well documented in Japanese texts is the hunt for vintage clothing in the 1980s and 1990s. That world still retains a bit of secrecy, but I managed to talk to a handful of key people to craft a general narrative.

Why do you think American style caught on so quickly after the war?

One of the big misconceptions I hope to clear up with Ametora is that for the first two decades after the Occupation, the vast majority of Japanese men did not adopt American styles. In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, only a small number of delinquents copied styles from American soldiers. Normally, students wore black uniforms, and adults wore vaguely British-style suits. It wasn’t until Kensuke Ishizu of VAN Jacket intentionally brought Ivy League style to Japan in the early 1960s did middle-class Japanese youth start to wear American-style clothing.

The Occupation certainly shaped Japan and set it up for cultural exchange with the U.S., but the spread of American styles was not “organic.” In fact, the more distance from the Occupation, the faster the adoption. By the mid-1960s, there were very few Americans in Japan, and so for a huge population of baby boomers, America did not represent an occupying army and the ignoble defeat of the war, but rather an imaginary, fantasy country far away with vast wealth, great music, and trendy clothing.

One of the themes in your book is about how Japan’s “obsession” with American style is sometimes not really about America at all. Can you elaborate on this point?

The vast majority of Japanese consumers learned about American style by seeing other Japanese people wear it, rather than seeing Americans. So in the 1960s, Ivy went mainstream because young Japanese men read the magazines Men’s Club and Heibon Punch, both filled with Japanese models wearing the clothes, and would go to Japanese stores, such as Teijin Men’s Shop, to buy the Japanese brand VAN Jacket. Classic rock’n’roll style came in during the 1970s because of the singer Eikichi Yazawa and his band Carol rather than any direct contact with American greasers or Elvis.

As an economic powerhouse, the US has enjoyed the power to legitimize and evangelize its own pop culture more than other countries, but that culture spreads much faster overseas when it becomes rooted in local culture. Japanese fashion has shown that certain individuals pulled culture from the U.S. and then introduced that culture locally in a very Japanese way, which helped it spread across the country.

You have a great chapter on how a little-known publication called Whole Earth Catalog helped set up the catalog format of many Japanese magazines today. In that chapter, you talk about how these publications were criticized for their fetishization of products – and yet, oddly, a lot of people today feel that Japanese publications are better than their American counterparts. Do you think that’s just because we live in a very product-focused age, or have Japanese editors managed to create better publications despite that focus on consumerism?

Yes, I think that the intense product obsession in Seventies Japan is now a standard part of global culture. But the reason that Japanese magazines look so good is that there have never really been “pure” fashion magazines in the US for men like what you see in Japan. GQ and Esquire have always had a lot more beyond clothing. The Internet has made a huge difference because sites like Hypebeast or Four Pins (R.I.P.) can do daily posts on new products. These sites are beloved, because they let you shop before you go to a store, and that was always why Japanese readers loved catalog magazines.

Why do you think clothing has become such an important subculture in Japan?

I don’t think menswear in Japan is a subculture or cult the way it is in the U.S. at the moment. Dressing well is very much mainstream, and even if the average Japanese guy may not be a nerd for designer labels, he is going to take his wardrobe relatively seriously. Even people without interest in clothing are likely to go to Beams or United Arrows and just pick out a few things that may be considered relatively fashion forward in the U.S.

Ametora goes through exactly why this happened, but I do think there’s a long history in Japan of clothing being important for demonstrating social rank and position. And in the postwar period, most people could not afford to buy cars or really decorate their homes, and so all youth energy went to buying music and clothing. When you’re in a big city like Tokyo, your clothing is basically your only way to show people who you are.

You’ve been posting some great photos on Twitter. Can you explain what we’re seeing in some of these images?

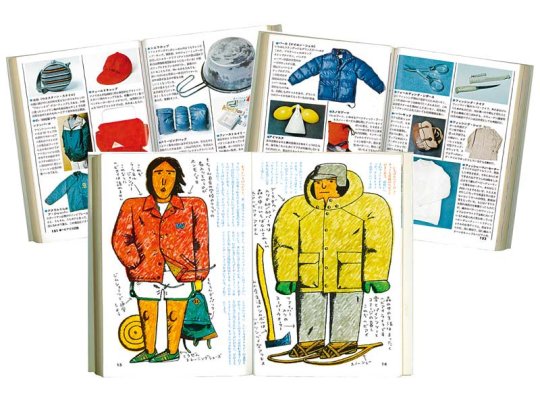

Heavy Duty: These are pages from

illustrator Yasuhiko Kobayashi’s “Heavy Duty Book.” Kobayashi helped

bring American outdoor style to Japan, which he packaged under the term “heavy duty.” He was a big outdoorsman, and meant his columns and books

to be a way to encourage people to go outside and enjoy camping and

hiking, but his young followers were only really interested in figuring

out what down jackets and 60/40 parkas to wear out in Ginza.

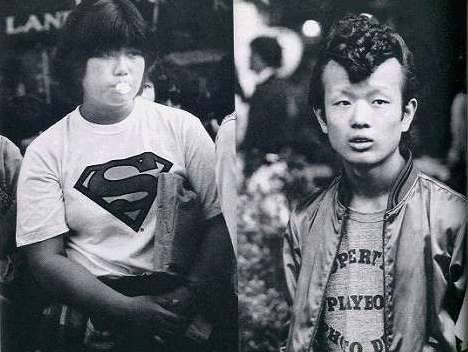

Shinjuku hippies: The Shinjuku neighborhood of Tokyo became ground zero for the hippie

drop-out movement in the late 1960s to early 1970s — a mix of local

bohemian values with imported American styles. Here you see a bunch of

long-hair types in surplus military and denim jackets. And with very

little in the way of recreational drugs, they liked to huff paint

thinner in plastic bags.

Harajuku UFO: Harajuku today is essentially the

world’s only entire neighborhood dedicated to youth fashion, but it

only really exploded in the mid-1970s with the rise of the rock ‘n’ roll

boom. Harajuku became both home to designer brands and underground chic,

but also delinquent kids dancing in rock ‘n’ roll groups in nearby

Yoyogi Park. This photo is from a rare photo book called Harajuku UFO, which is filled with amateur photographs of delinquent kids hanging out there.

The guy on the right is wearing his hair in the classic “regent”

pompadour style.

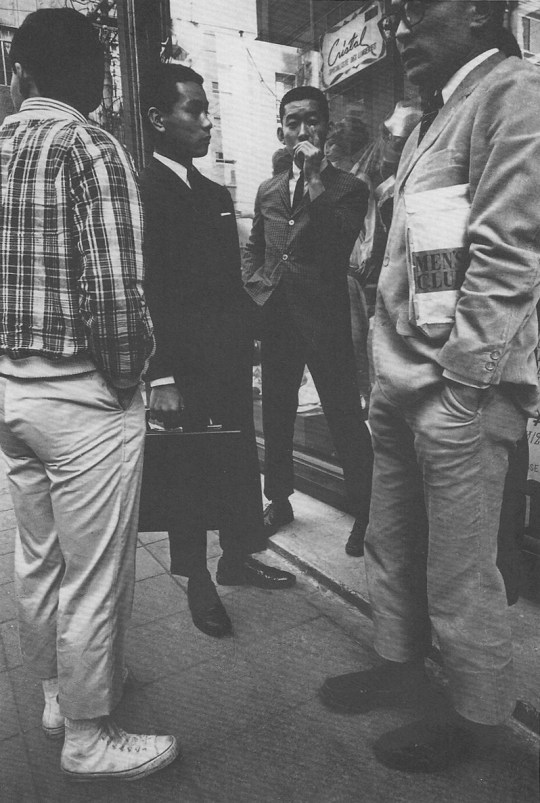

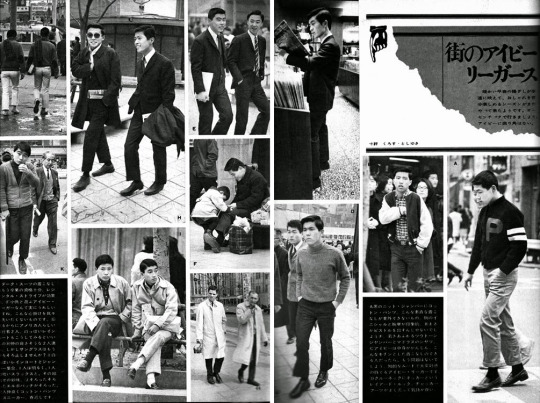

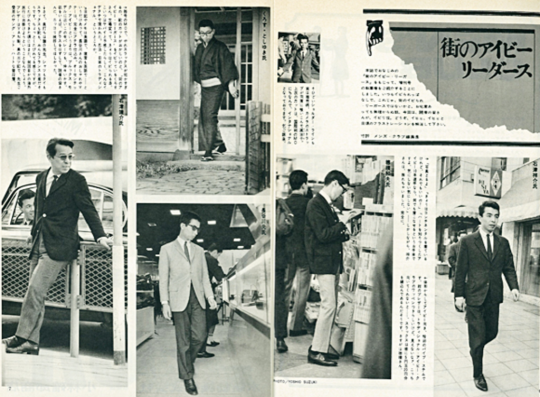

Men’s Club Ivy Leaguers on the Street: Men’s Club started Japan’s first “street

snaps” column in 1963 to show kids that real people actually wore the

Ivy League style they advocated. And so every month they would show

fifteen to twenty stylish kids, while Toshiyuki Kurosu wrote explanatory notes. This

example is Men’s Club’s self-parody of the column, since all the people

included are members of VAN Jacket and their friends. Here you see (from

left to right, top to bottom): Kensuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, Paul

Hasegawa, Kazuo Hozumi, and Shosuke Ishizu.

It feels like Americana, prep, and denim have somewhat receded as trends in the US. Are they still important in Japan?

At this point, the Japanese fashion market is so big and diverse that it includes literally everything. Old guys buy replicas of VAN Jacket clothing from the 1960s, middle-age guys buy hardcore repro denim, young guys buy a single Thom Browne shirt and wear it untucked over shorts. A lot of American styles are just so buried into the fashion culture that they are equally common in Japan as they are in the U.S. But at the same time, the editors and stylists at Popeye are now trying to do something very different than just historical Americana or even copy current American trends.

What’s next for you? Are you working on any new projects and will you continue to write about men’s style? Are you still focusing on Japanese fashion or are you shifting to other things?

I’ve been running a web journal on Japanese culture called Néojaponisme with the graphic designer Ian Lynam for almost a decade, and this year we’re going to try to go “offline” with some interesting things. Most of the things I’ll do on men’s style will be supplemental material to Ametora. And then I’ll be slowly doing some research for a broader future book on the mechanics of cultural change.

Special thanks to David for his time! You can follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and Néojaponisme, and find his book at Amazon.

(Photos via Warby Parker, Gus Walbolt, Ivy Style, and W. David Marx)