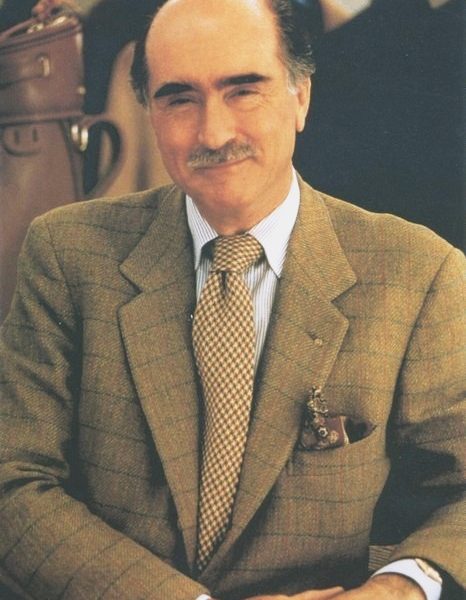

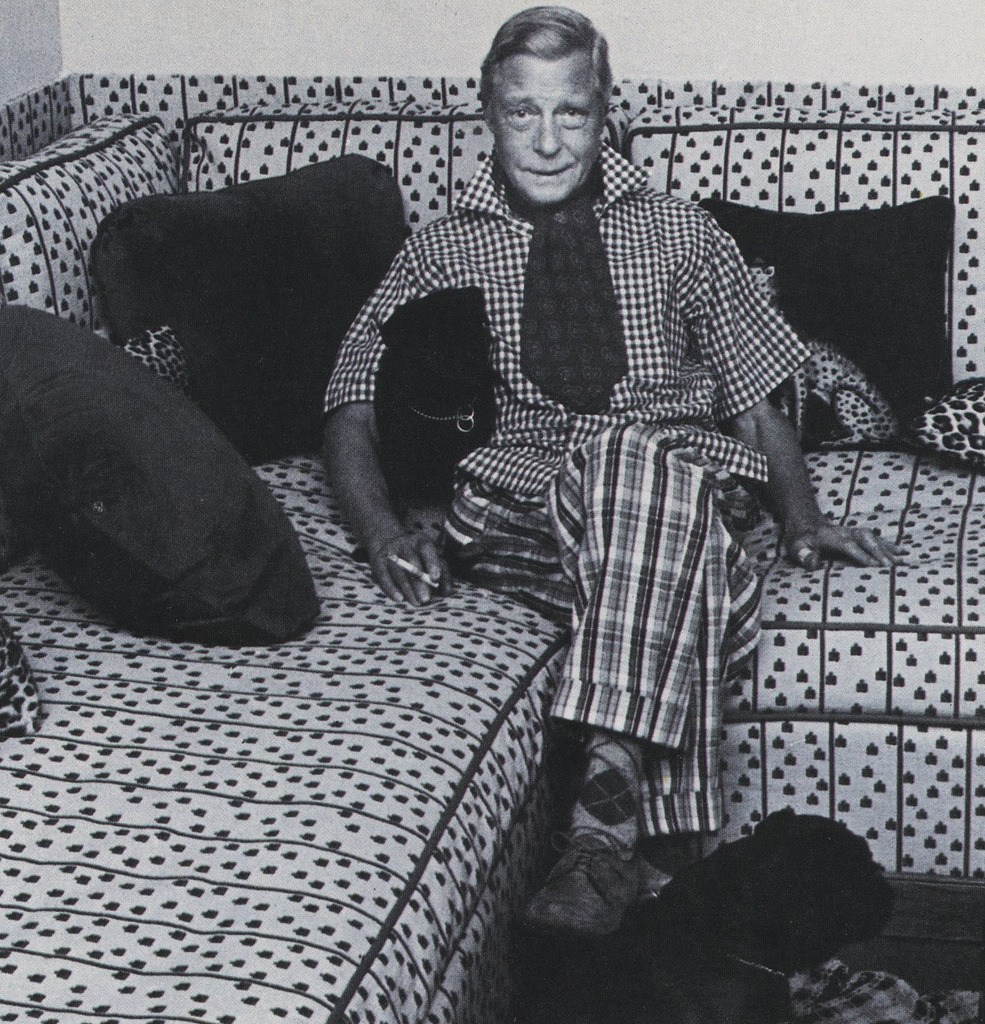

The latest episode of our second season, titled “Eccentric Style”, comes at a good time for me. I’ve been wanting to talk about this fantastically good Styleforum thread on the subject of complex pattern coordination. Not that combining four or five patterns necessarily brands one an eccentric. Indeed, one of my personal style heroes, Luciano Barbera, often mixes numerous patterns without making it seem unusual at all. On the other hand, Tom Wolfe, who arguably has a bit of an eccentric style, is often seen carrying no more than one or two patterns at a time.

Still, a high level of pattern mixing is more in the realm of eccentric style than not, and learning how to pull off complex combinations is worth discussion.

The rules are basic enough, and the principles for mixing many patterns stem from the ones we have for mixing just a couple. For example, two patterns of the same design (stripe on stripe, or checks on checks) can be combined if their scales are as different as possible. This avoids that terrible vibrating effect that can strain the eyes when too many patterns are present. So, a repp stripe tie with thick block stripes can be put on top of a Bengal striped shirt, or a puppytooth check tie can pair with a large windowpane suit.

Mixing two different patterns (stripes with checks) has the opposite rule. Rather than differ, the scales should be similar. This allows some contrast while still maintaining harmony. The only exception is particularly small-scale patterns, which can again distort the eye when two are placed too closely to each other.

From there we have the principles for mixing three or four patterns. Things should contrast, but also harmonize. If mixing three patterns where two are of the same design, vary the scale of two of the players – for example a hairline stripe shirt with a widely spaced chalk stripe suit. The third pattern can come in the form of a paisley or repp striped tie, so long the colors are complementary. For mixing three patterns of the same design, make all three vary in scale, perhaps letting them graduate from small to large as your ensembles moves outwards (shirt having the smallest scale; sport jacket medium; tie large). To get a fourth pattern, you can swap out the tie for a dissimilar design, and throw in a pocket square with a complementary pattern for final effect.

Of course, scale isn’t the only dimension to consider. There’s also texture, vibrancy, and color. A patterned woolen will look quite different from a patterned worsted, for example, and these things should be taken into consideration. But that entails a treatise that I’m not prepared to write, which is why your best bet is to follow the discussion here and observe the examples that some of the more astute StyleForum members have posted.