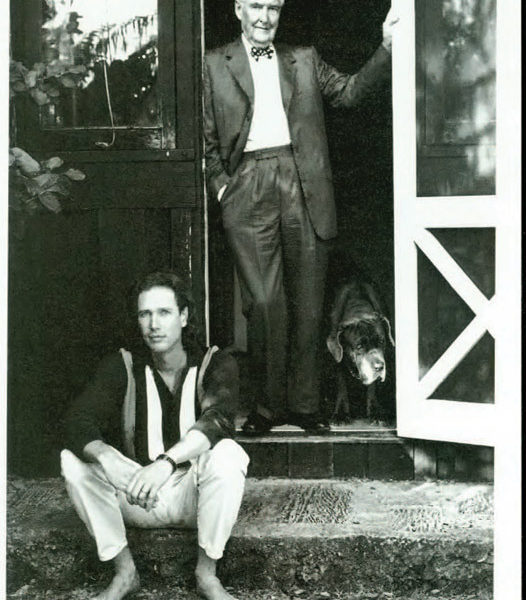

From a March 16th, 1998 article of The New Yorker, John Seabrook pens this amazing piece titled “My Father’s Closet.” It’s partly about his father’s closet, partly about his personality, and partly about how he – John Seabrook – came to find that he inherited his father’s penchant for clothing (if not his style). An excerpt:

As with most bespoke suits, each jacket has the exact day, month, and year it was ordered marked on the inside pocket. You can stand in the doorway, press a button, and watch as the history of my father, in the form of suits from all the different eras of his life, moves slowly past you. Drape suits, lounge suits, and sack suits, in worsted, serge, and gabardine; white linen suits for Palm Beach and Jamaica before the invention of air-conditioning; Glen plaids and knee-length loden coats for brisk Princeton-Harvard football games and a raccoon coat for Princeton-Dartmouth, which was later in the season. Suits for a variety of business occasions, from wowing prospective underwriters with a new offering (flashy pinstripes) to mollifying angry shareholders whose stock was diluted by the offering (humble sharkskin). Then, as the life-is-clothes approach succeeded at the office, suits for increasingly rarefied social events, from weddings at eleven and open-casket “viewings” at seven, to christenings, confirmations, and commencements, culminating in the outfits needed for four-in-hand driving, in which four horses are harnessed to a carriage–a sport that presents one with a daunting range of wardrobe challenges, determined by what time of day the driving event is taking place, whether it’s in the country or in town, whether one is a spectator or a participant, or a member or a guest of the club putting it on. Three-quarter-length cutaway coats, striped trousers, fancy waistcoats, top hats: his four-in-hand outfits are the part of his closet that verge on pure costume.

In a nearby closet are his shirts, made by Sulka or Lesserson or Turnbull & Asser; another closet contains a silken waterfall of neckties of every imaginable hue; still another holds shoe racks, starting at the bottom with canvas-and-leather newmarket boots and then rising in layers of elegance, through brown ankle-high turf shoes, reversed calf-quarter brogues, medallion toe-capped shoes with thick crêpe soles, and black wingtips with curved vamp borders, to the patent-leather dancing pumps at the top.

When he wasn’t dressed up, my father was either in pajamas (sensible cotton pajamas like the ones Jimmy Stewart wears in “Rear Window”) or naked. He was often naked. He embarrassed not a few of my friends by insisting on swimming naked in the pool when they were using it. But his nakedness was also a form of clothes, in the sense that it was a spectacle. Dressing without regard to clothes at all, occupying that great middle ground between dressed and undressed–dressing just to be warm or comfortable, which is the way most people wear clothes–did not seem to make sense to him.

Read the whole piece here.

(via Keikari)