After Saturday’s post on the coming 1930s fashion exhibit, I spent some time re-watching clips from our second season. I’m really proud of our videos, although I have nothing to do with their production. All the credit there goes to Jesse, Ben, Dave, and the many people who contributed to our funding.

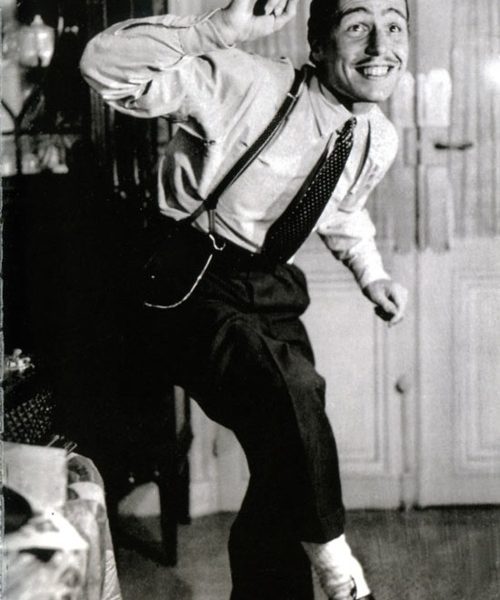

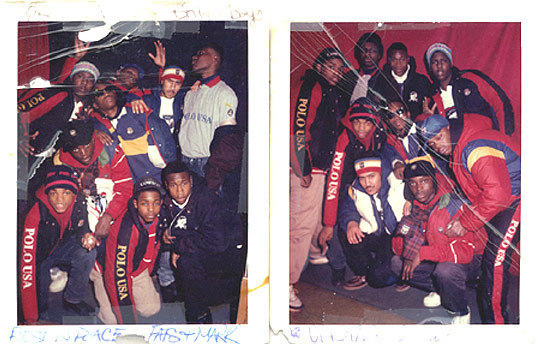

One of my favorite segments is our feature on ‘Lo Heads – a type of person who collects Polo Ralph Lauren clothing, often the pieces made between the years of 1992 and ‘94. Growing up in the ’90s, I actually had a number of friends that were ‘Lo Heads. At the time in Los Angeles, collecting and wearing Polo was very much connected to a particular underground dance scene, and I spent much of my youth going to clubs to watch guys dance in the flashiest Ralph Lauren gear you can imagine.

Our feature was poorly received by some readers, which prompted Jesse to write a thoughtful piece on the discursive act of dressing, and what it means for a population of young, (mostly) Black men to obsess over what’s (largely) a white line of clothing. I refrained from writing anything because – it seems to me – like many things dealing with youth subcultures, you either identify with it or you don’t. I liked the segment simply because it reminded me of my time as a teenager.

But upon revisiting the video, and thinking about sartorial history, it struck me that perhaps there’s something else to be said about the way we judge fashion.

Since fashion is often a game of one-upmanship, traits that start off modestly soon become exaggerated. So it was with the drape cut, which begat the zoot suit. Inches of fabric were added to the chest; the jacket was lengthened down to the thighs; the sleeves were made so full that they looked like trouser legs. It was a style calculated to be bold and outrageous – perfect for a youth subculture – and it really caught on with young Italians, Blacks, and Latinos, who at the time occupied the “lower” tiers of American social order.

The story of the zoot suit isn’t just about how a certain cut caught on, however. It’s also about politics. At the height of the zoot suit’s popularity (the 1940s), the US government had rationing programs so that raw materials could be conserved for the war effort. This was doubly true in England, where “make do and mend” were the watchwords that set style trends.

The result was a sartorial conflict. While most men were tastefully sacrificing things like pleats, so that less cloth was needed to make pants, these youths were walking around in suits big enough to fit two people. To those not of the culture, it looked unpatriotic and conspicuously extravagant, particularly for men who presumably had little money.

There was also a lot of racial identity tied to the zoot suit. Although some whites wore it, it was largely identified with Blacks and Latinos. When telling the story of zoot suits, it’s hard to not mention people’s attitudes towards race and class. The Zoot Suit Riots, which left more than 150 people injured, were just as much about rising tensions between whites and Latinos as they were about people’s attitudes towards the war.

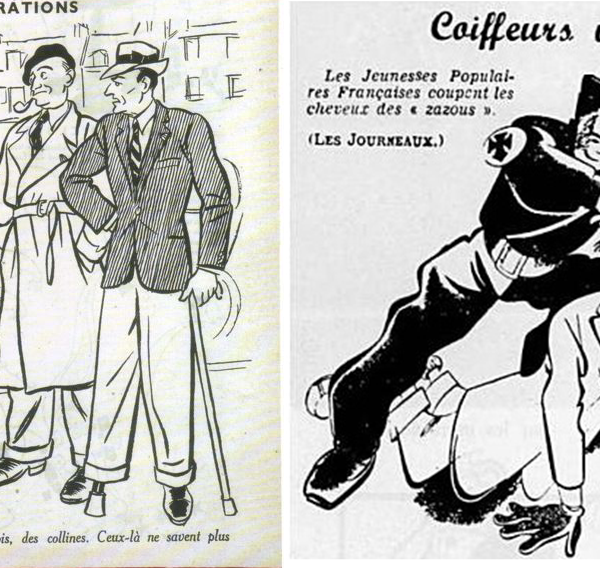

There’s actually a somewhat similar story in Nazi-occupied France, where young Parisians known as les zazous sported a zoot-suit-esque fashion. Les zazous too were rebelling against the (Vichy) government’s decree for rationing. Their choice in clothing wasn’t disliked just because it required a lot of cloth however, but also because it represented a bigger “threat” to a society. Vichy government supporters viewed it as being part and parcel with other “bad” things – degenerate taste in music and language (as such youths listened to jazz and used American slang), laziness, and a sympathy towards Jews.

Above are some cartoons from anti-zazous publications, one of which shows a policeman forcefully shaving off a young man’s long hair, which at the time was viewed as an identifier of these “jazz-loving, slang-using, work-avoiding, Jew-befriending” youths and their morality.

I’m not enough of a relativist to say that everything is subjective. In many ways, the baggy cut of the zoot suit looks outright silly. And, I can imagine that if you didn’t grow up in a culture with ‘Lo Heads, that sort of dress can look strange as well. At the same time, it can be difficult to view any of these things without our pre-existing biases on class. In other words, how we feel about certain fashions – what is “good taste” or “bad taste” – is often deeply tied to how we feel about the people wearing those said fashions in the first place.

Let’s be clear: I’m not accusing the critics of our video of being racist or classist, any more than I’d want to be accused of being racist or classist for liking the dress practices of old-money Anglo-Americans. I’m simply saying it’s hard to set aside our pre-existing social or political views when it comes to judging fashion, style, or taste. All dressing comes in a cultural context – it’s a context we inherit and sometimes have to look hard to see.

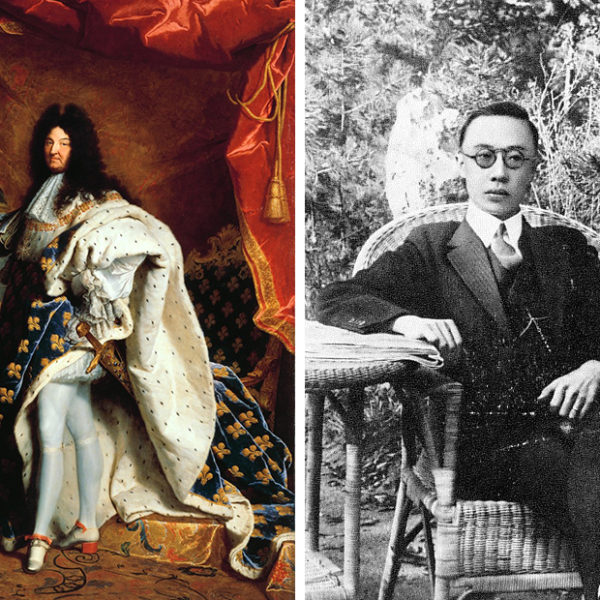

If you’re not convinced, ask yourself how did everyone come to dress like English gentlemen? How did the colorful, extravagant garb ofmen – from French kings to Chinese nobles – give way to the austere, drab clothes that British aristocrats favor? It’s hard to explain this without talking about the rise of the Second British Empire (1783-1815) and Britain’s imperial century (1815-1914), and how people around the world subsequently came to view aristocratic British values and culture.

Or set aside the world, and ask how the suit came to symbolize authority and power within the narrower context of British society. British men of a certain class used to wear frock coats – a knee-length suit jacket style that was popular during 18th and 19th centuries. Then, a Scottish socialist named Keir Hardie wore the lounge suit (what we think of today as the business suit) to Parliament as an MP in 1892. It was controversial, but he did so to signal his solidarity with ordinary workingmen. A few decades later, the young heir Edward VIII wore the lounge suit as a sort of rebellion against his father the king (who upheld social norms by wearingmuch more formal clothes). The lounge suit was considered too casual for someone of Edward VIII’s class, and his father hated him for wearing it, but he was so often photographed in a lounge suit that it became acceptable for other men of power to wear it as well. It’s a legacy that continues today, as the lounge suit is pretty much the de-facto uniform for presidents, prime ministers, and kings.

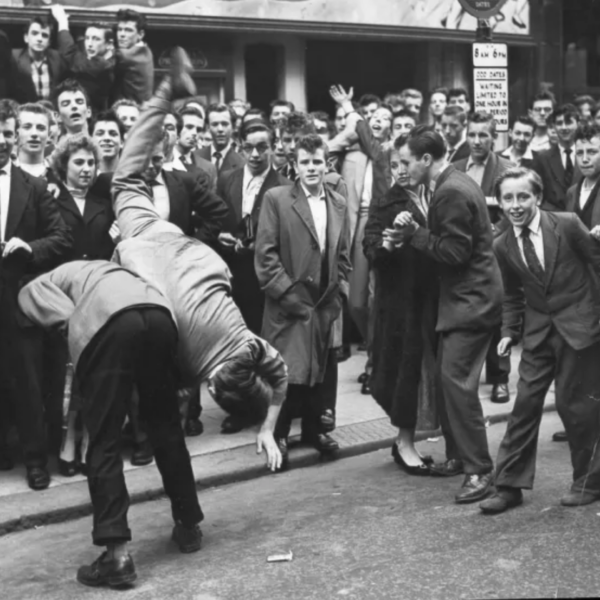

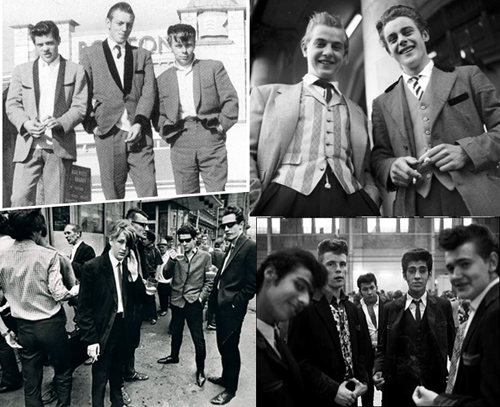

The unwelcomed co-optation of upper-class style by ‘Lo Heads is hardly new. In London in the 1950s, young men from poorer sections of English society started wearing old Edwardian fashions. They were known as “Teddy Boys” and they dressed in a style that some Savile Row clients grew to after WWII (of course, because they lacked money, Teddy Boys did not get their clothes from Savile Row). The Teddy Boys were characterized by drainpipe trousers, long jackets, pointed collars, and fancy waistcoats. There’s a great BBC segment on them here.

The sartorial choices of the Teddy Boys and ‘Lo Heads were received by their respective societies in much the same way: that is, not well. It’s not surprising because, for most people, these were not well-regarded groups to begin with. Our attitudes about how someone dresses is often just as much about how we feel about that person’s background as it is about the “objective” fashion itself. And frankly, the underlying tension of class is why Teddy Boys and ‘Lo Heads dress the way they do in the first place. That twisting of the style and its meaning is … kind of the point.