After Jesse posted about our Japanese textile scarves on Monday, I found myself Googling around for more info about boro – that wonderfully old, patched up fabric that comes out of Japan’s countrysides. Somehow, I stumbled upon the website for Orime, a small, Boston showroom that specializes in antique Japanese textiles and mingei items (mingei being the term for an early-20th century Japanese philosophy that celebrated the beauty in everyday utilitarian objects – sort of like a Japanese counterpart to England’s Arts & Crafts movement).

Orime is run by two partners, Jared and Christopher, who have been collecting Japanese folk textiles for about ten years now. Up until very recently, they mostly sold things out of their showroom and at the Antique Textiles and Vintage Fashions show in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Earlier this year, however, they launched an online shop. No small feat, as their inventory is large and it takes a lot of time to correctly photograph and document each item (even the stuff up now is only a fraction of what they actually have). Fascinated by their site, I called Jared and asked if he could give us a lowdown on some of the pieces. He kindly took us through the craft techniques used in some of these magnificent items.

BORO: Boro comes out of Japan’s countrysides, where cloth used to be very precious and valuable. Since disposing things wasn’t an option for a lot of poor families, the wives of farmer and fisherman would patch and mend futon covers, clothes, and bags. As a result, you get these beautiful objects with hundreds of shades of color, often patched together with rough running stitches.

“Boro is less about a craft technique than it is an idea,” explains Jared. “It’s about repurposing rags or salvaging cloth, which was done out of necessity, not beauty. So while we typically see boros made from indigo-based cottons, they can really be made out of anything.”

Pictured above: A boro futon cover that has been heavily patched and mended using an array of fabrics – from striped to solid-colored cottons. Also a farmer’s work jacket, known as a noragi, which has been patched together using dozens of late-19th and early-20th century rags.

KASURI: A Japanese form of ikat, where threads have been resist-dyed prior to being woven. “Kasuri can be done by using resist-dyed threads along the weft only, or along the weft and warp. The second technique will produce a more detailed image, but – even with a skilled worker – the edges will always be slightly blurry. Part of the look is about the slightly diffused edges you see in the pattern,” Jared explains.

Pictured above: Two kasuri futon covers, made from threads that have been hand bound, dyed with botanical indigo, and then woven on a hand-loom.

KATAZOME: Another resist-dye technique. This is done by applying a rice paste through a stencil. The paste is allowed to dry, and then the fabric is dyed. One the color has been set, the paste is removed, thus revealing the design.

Stencils used are typically small (maybe about the size of a sheet of paper). They’re set along, edge-to-edge, on the fabric as the worker applies the paste. On really good examples, the pattern will be applied to both the front and backsides of the cloth, and the stencils will align perfectly. Jared notes that sometimes multiple dyes will also be used. “Sometimes the person will apply one pass with a stencil, dye the fabric, and then apply another pass using a different color. In this way, you can get a build-up of colors, maybe a base design and then a highlight.”

Pictured above: Some lengths of hand-woven cottons, made out of hand-spun materials, that have been stenciled and then resist-dyed. Japanese textiles often feature petalled designs found in nature. The chrysanthemums in the top image, for example, are celebrated in Japan as a symbol of longevity. In the middle photo, we have a haten jacket, which features the Chinese zodiac kanji character for pig.

SAKIORI: A Japanese version of rag weaving, done with narrow strips of shredded cloth. This technique was popular when fabric was precious and people couldn’t throw things away. “For example, if you had an old kimono, you might salvage the fabric by tearing it into strips and weaving the bits together,” says Jared. “So the warp would be cotton yarn, and the weft would be rag strips, giving the fabric a sort of irregular coloring.”

Pictured above: A vibrant kimono sash. The cotton warp alternates between maroons and whites, while the shredded silk weft mixes deep purples, crimson reds, pine greens, goldenrods, and bright oranges.

SASHIKO: A rough running stitch that’s used to either repair or reinforce fabric, or as a way to add decorative elements. This can be applied to any kind of traditional fabric, although you most commonly see it in patched up boro covers and jackets (where the stitches serve a functional, structural purpose).

Pictured above: A wrapping cloth that has been beautifully decorated with a sashiko stitch to show a variety of patterns – overlapping circles, stylized chrysanthemums, and an interlocking motif of leaves. In the third photo, we see a grid of sashiko stitches that have been used to hold multiple layers of cotton together (this was done on a work jacket).

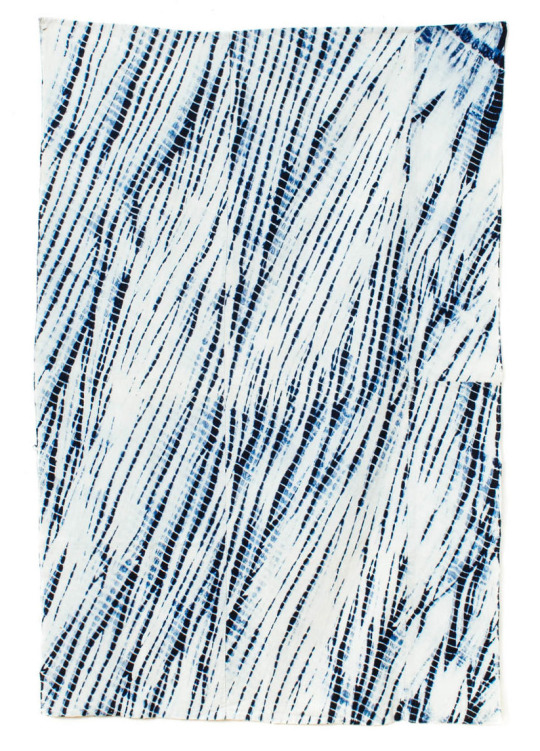

SHIBORI: Similar to tie-dye, although not strictly the same. Whereas tie-dye refers to a method of tying a fabric before dyeing it, the Japanese method of shibori can involve tying, pleating, or even wrapping the material around a pole. The result are these beautifully complex and repeating patterns you see here.

Pictured above: A vintage kimono and a length of cotton that Orime believes might have been intended for use as a rain cape. The cape features an irregular pattern that’s reminiscent of the cascading branches on a weeping willow. The pattern was achieved by hand-pleating the fabric and binding it with thread, before then dyeing the textile in indigo.

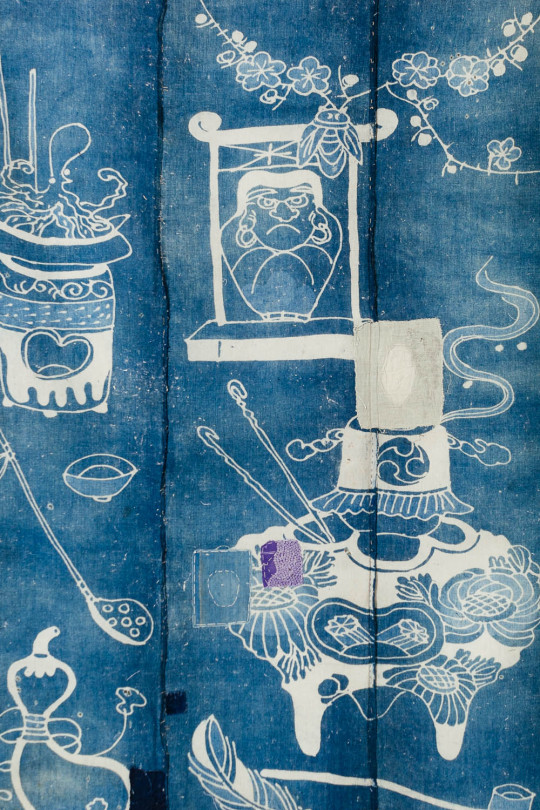

TSUTSUGAKI: Basically the same as katazome, but instead of applying a rice paste through a stencil, it’s applied freehand. “Think of it like applying icing on a cake, where you squeeze icing out of bag,” says Jared. Once the dye-resist paste is allowed to dry, the fabric is then dyed. The blue parts you see here are indigo, while the white parts are the natural colors of the fabric (where the paste was originally applied).

Pictured above: A work jacket and futon cover. The cover is decorated with various elements from Japanese tea ceremonies – tea whisks, water ladles, hanging scrolls, calligraphy brushes, and floral arrangements. Futons decorated in this fashion were often given as part of a wedding trousseau to a new bride and groom.

For more amazing photos, check out Orime’s website. They also have an appointment-only showroom in Boston and regularly show at the Antique Textiles and Vintage Fashion event in Sturbridge (which happens twice a year). For those outside of Massachusetts, you can follow Orime on Instagram and Facebook. Everything they post is available for sale, so feel free to contact them if you’re interested in something.

(Many thanks to Jared for taking the time to chat with us!)