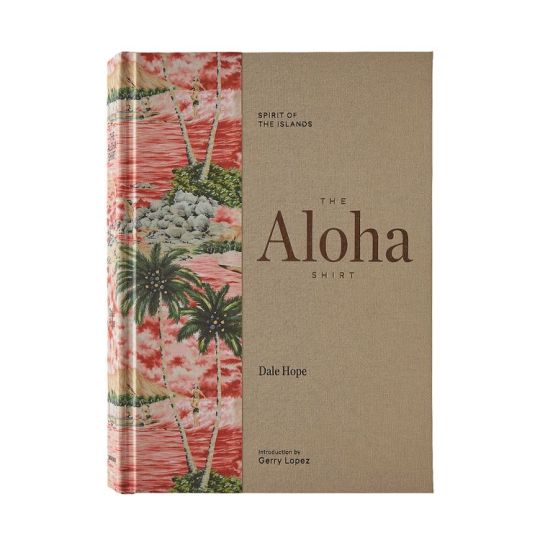

To call something a coffee table book is sometimes damning: coffee table books are pretty and hefty but the format—large, lots of pictures, more rewarding to flip through than read cover to cover—is fit for subjects for which there’s more to see than to say. Fortunately Dale Hope’s book on Hawaii’s most recognizable garment drops a lot of knowledge alongside its photos of vivid, intricately printed Aloha shirts, even if some topics are treated lightly. Originally published in 2000, The Aloha Shirt has been updated and reprinted by Patagonia this year—we received a copy for review (we’ve endorsed vacation shirts before).

Origins

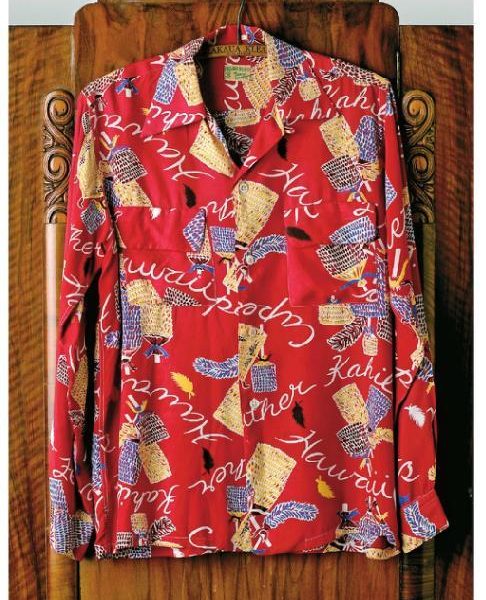

The book is heavy with history. Over years of research, Hope, a Hawaiian garment industry veteran, spoke with the families of the original makers of Aloha shirts. He traces the shirt from its roots in the early 20th century, when garment makers in Hawaii sewed “palaka” plaid work shirts for field workers (sugarcane and pineapples predated tourism as Hawaii’s big industries), through the influence of “pareu” printed fabric that came to Hawaii from England via Tahiti, and eventually the booming tourism industry—some of the earliest modern aloha shirts were printed with images of the ships that brought mainlanders to Hawaii; passengers would buy the shirts as souvenirs. Although who made the first Aloha shirt is disputed, the earliest Aloha shirts were the products of custom tailors, often Japanese or Chinese, making warm weather appropriate shirts for tourists–loose fitting, open collar, short sleeve, to be worn tails out, often in kimono-like fabrics of crepe rayon or silk.

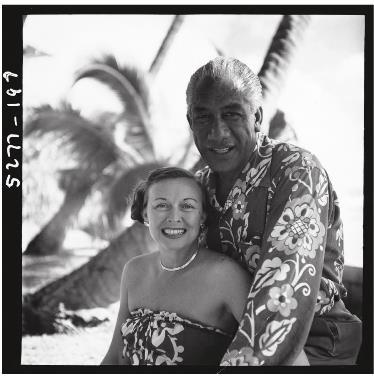

There’s not a decisive moment when the aloha shirt became the definitive Hawaiian clothing item, but it coincided with the mainland American fascination with the islands and the eventual export of Hawaiian culture. In the early part of the 20th century, Hawaii was a glamorous and exotic destination popular with the first generation of Hollywood celebrities–certainly that played a part, and Hope includes a gallery of celebrities in aloha shirts, on and offscreen. With the military presence in Pearl Harbor and the Pacific theater of World War II, servicemen would buy their off-duty clothes locally, and brought those shirts back to the states when they came home. After the war, as air travel made Hawaii more accessible and the Hawaiian sport of surfing rolled onto the west coast, the shirts became signifiers of identification with that subculture rather than wealth and travel. The shirts, initially carried only in Hawaiian shops, could eventually be found in Sears all over the country.

The Makers

Hope’s book is less concerned with the anatomy of a trend than the individual stories of makers, retailers, and designers in Hawaii, and the community they built to meet the demand for Aloha shirts. The books tells of Musa-Shiya the Shirtmaker, a Japanese tailor who was first to advertise print-cloth shirts as “Aloha” shirts. Hawaii had a significant Chinese and Japanese immigrant population, and a lot of the same tailors and small-scale factories that initially made Aloha shirts also sewed kimonos, and ordered their print fabric from Japan. Some of the oddities of these early prints can be chalked up to Japanese fabric designers trying to interpret descriptions of Hawaii—a place and people they would never actually see. Similarly, a lot of Aloha shirts feature motifs that are more Asian than islander—tigers, cranes, Mt. Fuji.

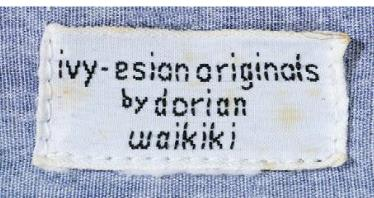

Hope also includes spreads on individual, innovative brands and shops like Branfleet, Surfriders, Kahala; designers like Elsie Das; and fabric makers like Alfred Shaheen. He tries to sort out the sometimes contested origin stories of certain aloha shirt aspects, for example, the reverse prints in the 1960s are attributed to bartender Pat Dorian—

Another tale says the reverse prints were originally a manufacturing accident that just worked. See the Dorian label above for an Ivy style crossover—Reyn Spooner popularized buttondown collar popover aloha shirts in the 1960s, actually borrowing the shirt pattern directly from Gant, with Gant’s approval. These sections will give you a great list of vintage labels to search for on eBay and in thrift stores.

The Designs

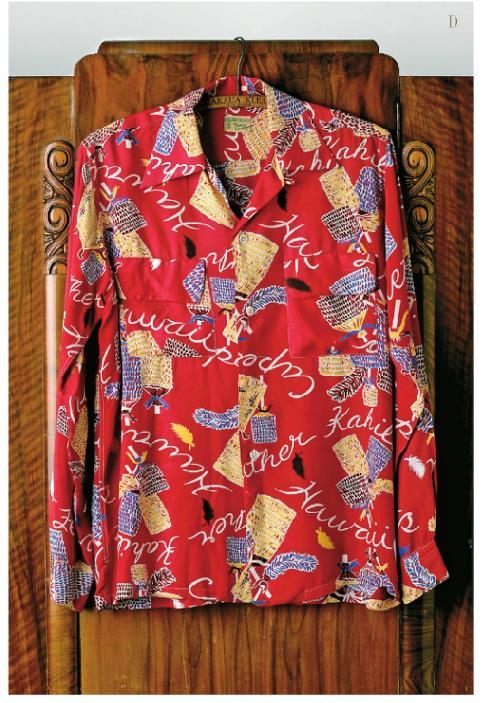

Regarding the quality of designs and prints, Hope mostly lets the selection of vintage shirts do the talking vs qualifying in language what makes a good or bad design. The photo captions helpfully explain what different prints are—by the end of the book you’ll have a better handle on differentiating your pineapple leaf form your breadfruit leaf. One 1956 newspaper article Hope quotes describes the process of designing eloquently:

“As in all art, there is no recipe for textile design… an artist considering his idea, for example, a flower form, no longer as a unit but as an element in a pattern. He will consider areas of dark and light color. He will determine the treatment of the flower: will it be stylized or realistic? He will select the particular technique to be used: textured, washed, or a line drawing. The number of colors will be considered and often a choice of fabric may be a factor… Often border patters will be selected for cotton or heavier materials, finer patterns will be reserved for finer cotton or silk.”

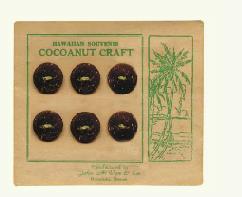

The chapter on collectors is the most informative on what connoisseurs look for in a classic Hawaiian shirt. Though not all collectors agree, most tastes reflect attributes of the “Golden Age” of Aloha shirts from the 1930s to 1950s–manufacture in Hawaii, silky (not silk) rayon fabric, quality coconut buttons, a pattern that flows naturally across the shirt, fine stitching, pattern matched pockets–many of the same sorts of things we look for in a quality dress shirt. My personal tastes run to the more subdued, Reyn Spooner style prints but you can’t deny the beauty of richly multi-colored prints or those that use the shirt’s panels as a continuous canvas for a landscape or other scene.

The Culture

For all the solid historical context, as a coffee table book there are some topics Hope’s book is just not set up to address. For example, it’s mentioned several times that Hawaiians themselves embraced Aloha shirts as a symbol of pride. The foreword by Gerry Lopez describes how he bought Aloha shirts in his high school thrift shop when he tore his own shirts in fights. But for a shirt with roots in both backbreaking agricultural industry and tourism catering to outsiders, I would like to hear more on Hawaiians’ feelings on appropriation. To be fair, the aloha shirt, made explicitly for tourists, is not a spiritually or culturally vital item in the way that, say, leis can be, or a Native American headdress would be.

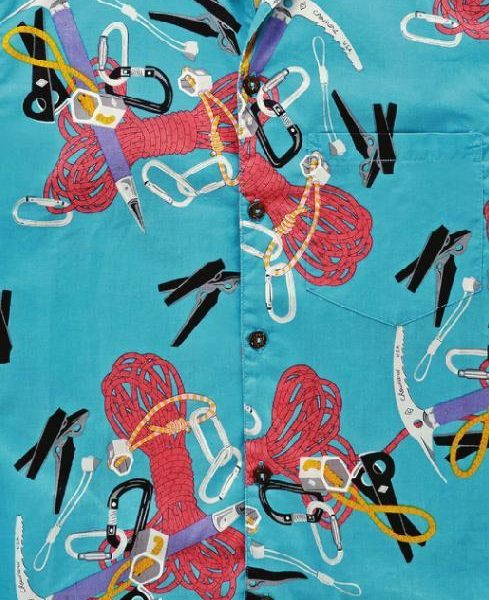

Hope was born and raised in Hawaii and spent his life in the garment industry there, so a focus on the rise and fall of elements of that industry makes sense, but it sometimes gets tedious to read several similar stories of startup shirtmakers innovating on one or another aspect of making shirts. Some of the details he focuses on–like fabric order minimums in Japan vs America in the 1950s–are interesting in a manufacturing sense but Hope doesn’t get into a lot of broader implications or effects of these issues. Lastly, although Hope has worked with modern designers like Patagonia (which gets a light chapter to itself) and Beams Japan, there’s not a lot of information on the broader influence on fashion of the Aloha shirt.

The galleries of photos—of vintage shirts and fabrics, of personalities like the great Duke Kahanamoku (above) who were influential in the spread of the Aloha shirt, and of Hawaii itself—make the book worthy of more than a quick browse on a coffee table. Now that I think about it, a reclaimed surfboard would make a pretty sweet place to rest a coffee cup and this book.