About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

About the menswear of the twentieth century, I can say this for sure: I don’t think I’d wear most of it. Neither would you, I imagine, unless you’ve thrown in your lot with the Brooklyn handlebar-mustache set, though in that case you’d have pledged allegiance to only a select set of time periods, stylistically compatible or otherwise. Reading through Cally Blackman’s 100 Years of Menswear exposes you to all of them, from 1900 up to the mid-2000s, breaking down their clothes by vocational and avocational inspiration: worker, soldier, artist, reformer, rebel, peacock, media star, and so on. This organizing scheme roots the shifting aesthetics of all menswear in functionality, a flattering assumption — no useless, free-floating design whims for us men, thank you very much, even us men who happen to be designers — but not necessarily an incorrect one. Suitable dress helps all of us do our jobs, and that holds truer still for full-time rebels and peacocks.

Even for quite a few of those rebels and peacocks, the most suitable form of dress remains, yes, the suit. “The three-piece suit, introduced and formalized in the late seventeenth century, has prospered for nearly 350 years because of its unique capacity for nuance and variation,” Blackman writes in the introduction. “To adapt a phrase from Le Corbusier, the suit is a machine for living in, close-fitting but comfortable armor, constantly revised and reinvented to be, literally, well-suited for modern daily life.” Yet twentieth-century menswear history tells, in large part, the story of the suit-wearing’s decline, which went especially precipitous in the late sixties. The pages of 100 Years of Menswear offer suits aplenty, both photographed and illustrated, in settings from the street to the workplace to (in a bizarre 1937 Esquire spread) the ski slopes, but they ultimately prioritize the diversity that the decades would let emerge: we see plus fours and pushed-up Miami Vice sleeves, tennis whites and motorcycle gear, Beatle boots and Nehru jackets – all, I suppose, the components of machines for living, albeit very different ways of doing it.

That said, nobody expects you to want to wear most of the menswear of the twentieth century. Though it doesn’t present itself as any kind of how-to, the book does contain images that may come in handy when you put together your next period costume. Turning up at the office party as Bryan Ferry in 1977, seen in Blackman’s selected photo evoking vintage gangsterism in a gray three-piece with viciously peaked lapels, strikes me as a particularly sound idea. But doesn’t that setup, a rock star deep in the glam years ordering his tailor of choice to evoke a bygone age of classy thuggishness, also offer a deeper kind of instruction? Examine the photos in 100 Years of Menswear systematically enough — for, despite its surprisingly meaty captions and chapter introductions, a photo book it remains — and you’ll get a feel for not just the way certain fashions periodically float to the top of the sartorial zeitgeist, but how other fashions exert influence within those fashions. One era’s peacock imitates another’s soldier; its rebel, another’s worker; its media star, another’s artist.

While Ferry has long displayed a knack for knowing when to draw upon his favorite bits of the past, his contemporary David Bowie more famously took this historical layering to its logical end. Since Blackman regards subculture as perhaps the most influential force on menswear, I might have expected her to include more than two pictures of the man who — as Ziggy Stardust, as Aladdin Sane, as the Thin White Duke, as whomever — not only made use of more subcultures than any other dresser, but created a few subcultures of his own. But you or I, out less to create subcultures than to simply dress with care, imitate the differently flamboyant likes of Ferry or Bowie at our peril. We’d do even worse to take as examples the outfits seen in Blackman’s final two chapters, covering stylists’ and designers’ experiments from 1940 to present. But the better we understand the ends of menswear’s various aesthetic axes, the better we can place ourselves in more tenable positions along them. At the very least, you can profit from the book’s penchant for extremity for its “what not to wear” (or at least “what to tone way down”) factor.

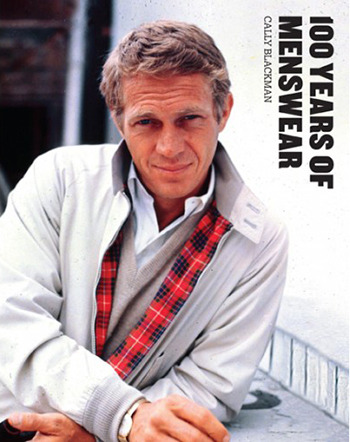

100 Years of Menswear also offers knowledge as a pure visual chronicle, and for such a project Blackman, a writer and teacher with previous books on general fashion, costume, illustration, and the styles of the twenties and thirties to her credit, has the credentials you’d expect. (As a non-man, she brings still more objectivity to the table.) But any book that pays equal attention to Andy Warhol, Edward VII, Miles Davis, Boy George, Mark Twain, and Marc Bolan risks coming off as a book insufficiently focused, and most serious dressers will narrow their attention to a particular chapter or two. I find myself returning most often to the pages on media stars, not just because all my own work involves media – though as noted above, our form will, ideally, fit our function – but because their dress tends to stand, or in any case once stood, the test of time. There we find a still of Cary Grant in North By Northwest, and Blackman reminds us that the icon “always wore his own clothes on screen,” “a testament to his faultless style and effortless elegance at a time when the stylist did not exist.” A better time, we might sigh, moving on to scrutinize an image of Steve McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair. The fact that another, even better-known photo of the era-defying McQueen graces the cover hints at where Blackman’s carefully concealed stylistic allegiance may lie. Then again, that same chapter devotes an entire page to Starsky and Hutch, so I wouldn’t make any bets.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy 100 Years of Menswear, you can find the best prices at DealOz.