An anonymous reader asks: Would you briefly explain the meaning of numbered fabrics (like super 150’s, 120’s, etc)? I’ve never seen a good article on this. Maybe you could point one out to me. Thanks very much!

Jesse has a knack for answering questions well and succinctly. I don’t have that knack, but will give you the best answer I can. I’ll take you through the history of Super wools, which I think is a fascinating story, as well as what it practically means for you. If you want the short answer, just skip to the takeaway section.

The History of Super Wools

The story behind “Super wools” is an incredible tale of how early periods of the global economy affected men’s clothing.

In 1789, King Charles IV of Spain gave two rams and four ewes to Colonel Gordon of the Dutch East India Company, who in turn brought them to South Africa. Six years later, Colonel Gordon died and the original six animals had by then become 26. His wife sold the flock to an enterprising British immigrant in Australia who would then use these animals to found the multi-billion wool industry in Australia today. Most of the middle- to high-end suits in the market these days use Australian wool, which means much of the tailored menswear industry can be traced back to the six animals that King Charles IV of Spain originally gave away as a gift.

However, that’s not the story of Super wools just yet; it’s only the background. Australia doesn’t weave wool, it only grows it. Once the wool has been shorn from sheep in Australia, it is typically sent off to Yorkshire, England (more specifically Huddersfield) to be spun into yarn, and this yarn is then woven into cloth. The innovation of “Supers” comes from this Yorkshire town, Huddersfield.

The traditional way of grading the quality of wool yarn in Huddersfield was to see how much could be spun out of one pound of raw wool. The finer the fibers, the most spools – or “hanks – could be filled. Thus, if a wool was "70s,” it meant that a pound of raw wool would yield 70 hanks. Not only would finer yarn give more hanks, but it also meant that it was softer and silkier to the touch.

For a many centuries, 60s wool was considered the best in the world. Through selective breeding, however, Australians were able to produce new generations of sheep with finer fleeces. This was the advent of 70s and 80s wool. Consumers at this point still weren’t aware of these distinctions, but people in the trade became obsessed with getting the first 100-count wool.

When it was finally achieved in the 1960s, Joseph Lumb & Sons and H. Lesser, two British companies, decided to market the suitings as “Lumb’s Huddersfield Super 100s.” Now, this is a completely arbitrary distinction. There’s nothing inherently more monumental about breaking the barrier between 90s and 100s than 80s to 90s. It just feels more monumental because our ten-count digit system adds another digit once we reach 100. The marketing of “Super wools” however really took off in Japan, where a few Savile Row tailors had outposts. The idea of a wool being “Super” conveyed that this stuff was the best. It made such an impression that early Japanese and Middle Eastern customers would buy bolts of this “super cloth” and give them as gifts.

The evolution of the Italian menswear industry at the time also affected the wool industry. After the war, Italy’s ready-to-wear menswear industry really took off. I’ve written a bit about the history of Italy’s most important brands, and if you read through my articles, you’ll notice how many of them went global after the war. These Italian firms heavily marketed their suits as being made of “Super wools.” It was, in a way, to help distinguish themselves as a “luxury” brand on the international market.

This market reaction from Japan and Italy, coupled with the improvements in loom technology in England and breeding practices in Australia drove the development of Super wools to a point where we’re now somewhere in the mid 200s. Quite a feat given that Mother Nature was only able to develop “60s wool” herself.

So What Does it Mean for You? The Orthodox View

The simple story here is that the higher the number given to the wool, the softer and silkier to the touch it will be. However, many say that the fineness of the wool means that it will break down faster. As you wear your Super wools, they’ll tend to get shinier in areas that get more stress or wear – like say the seat of your pants. Sometimes it will even wear straight through. It’s a “higher end” wool, but in this case, you trade short term luxury for long term durability. For customers who have a lot of money, this may not be really a big deal, and the tradeoff for luxury may be more valued. If you’ve ever handled a Super 120s and Super 200s, you’ll be impressed with how soft the higher count suiting feels against the skin.

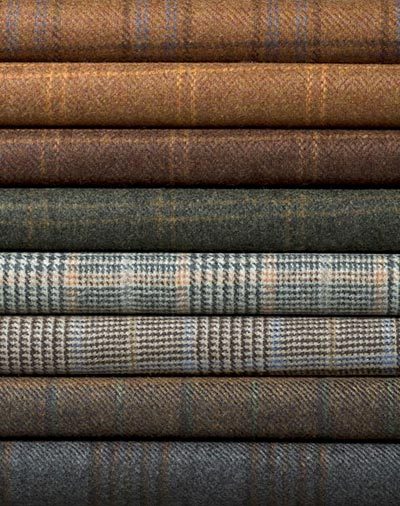

The other advantage of the higher count Super wools is that the the finer yards will allow weavers to get more intricate colors and designs into the fabric. Imagine then a customer going into a store – stroking and gazing at the soft, beautiful cloth, and being told that this was a “Super wool.” Who can resist?

The More Nuanced View of Super Wools

That’s the simple orthodoxy – super wools are more luxurious, but aren’t as durable. There’s a much more nuanced and sophisticated understanding, however.

First, remember that the way we measure wool comes from a centuries old practice that wasn’t particularly sophisticated. It wasn’t a very precise measure of fineness and to the degree it even did that job well, it only measured one aspect. There is more to the quality of wool than it’s thickness, however. For example, there is the length of the fiber. The longer the better, as it will be less likely to break. There is also the crimp, as a waviness to the wool will give it resilience; its consistency in the batch; the amount of natural oils in the fibers; how well its woven; so on and so forth. This point was very well proven in this article by Jeffery Diduch, one of the best sartorial minds around. In it, Diduch shows an old bespoke piece made of Super 150s wool. The lining has been worn straight through, but the wool is in near perfect condition. The suiting is clearly high quality and can’t be reduced to just a number.

Second, there is the issue of whether the numbers are even correctly reported. The Wall Street Journal had a great article five years ago about how suits designed as being of a particular “Super count” actually clocked in at a higher or lower number. This was found even in luxury end suits by Canali, one of the best off-the-rack Italian suit makers in the world. You have to wonder then whether what you’re buying is really the Supers designation that was given to it.

The Takeaway

So what’s the takeaway? Super wools refer to the fineness of the yarn, which in turn translates to how silky, soft, and complex the weave can be. However, there is more to the quality of wool yarn that how fine each fiber is. This means that you shouldn’t judge the quality of a suiting just from it’s “Supers” count – either adoring or dismissing it for its high numbers. Instead, you should just take it as one dimension. If you buy a nice Super 150s wool from a very good mill, it will wear fine, though perhaps not as well as a more traditional cloth in the 60s and 70s. There’s no reason to be afraid of it straight out of the gates, however. On the other hand, if you get a Super 150s suiting from a bad mill, you’re probably just being suckered into a marketing ploy. In the end, there is no quick label to tell you what to buy and what not to buy; you have to do your homework.