Authenticity, the holy grail of today’s marketing departments, is a slippery concept in menswear. Sometimes it refers to a brand’s heritage, sometimes it’s about design, and sometimes it’s about how things are worn. The readers at Ivy Style have always been quick to point out transgressions. Every deviation from the most authentic era of 1950s and ‘60s prep is vehemently railed against, whether readers lived through those periods or not. The comment section can get particularly rancorous — it’s often full of fights between posters who have rivalries stretching back many years. People argue about the roll of a button-down collar, where things should be manufactured, and whether something lives up to their notions of mid-century America.

Arguments about authenticity, however, turn dark when they become about who gets to participate in a style. This is particularly true of people who like Ivy not just for its look, but also what they think it represents. In a post about the film Dear White People, one commenter warned about the dangers of miscegenation, suggesting the film is another piece of Hollywood propaganda to convince “white women that black men are worthy of dating.” When asked what this has to do with button-downs and hook vents, the commenter replied: “is not the topic of our traditional American clothing — Ivy, Preppy, Trad — tied indelibly to our traditional American values?” Similarly, when LL Bean debuted their new marketing campaign in 2017, some complained about a black family appearing in the New England brand’s advertisements. And when Rowing Blazers, a sponsor on this site, collaborated with the streetwear label Noah, one reader was upset the proceeds were going to Row New York, a non-profit that encourages young, black kids to get into the sport of rowing. The comment read:

I want some things to be the exclusive province of the elite. I want an upper class with their distinguished modes of dress. Sure, teach urban kids from poor backgrounds how to row. But don’t pretend you’re elevating them by giving them a blazer to wear while at it. Authentic preppiness will always have middle- and upper-class connotations. I don’t get this zeal to universalise and equalise everything.

In the mid-2000s, prep was ascendant, riding on the heritage wave that was consumed with finding all things authentic. But “authentic prep” means different things to different people. For some, it’s about a slightly fuddy American look that never goes out of style. For others, it’s a symbol of an imagined 1950s America, when an apple pie sat cooling on every windowsill, race relations were perfect, and everyone knew their gender roles. In an old post about prep’s decline, Pete wrote about prep’s vaguely aspirational qualities, and how the public has a love-hate relationship with its elitism. “Prep stunts in ways that seem dated,” Pete wrote. “Prep implies privilege and inherited money; some of prep’s charm comes from the unquestioning self-confidence bestowed only by independent wealth. Americans have always had a weird relationship with being born into something versus earning it. Today we still like our wealth obnoxious. But not smug or entitled.” While that’s true of most people, there are some — MGTOW types, alt-right extremists, and frankly racists — who like prep not in spite of its associations with white privilege, but because of it.

Rowing Blazers and Neo Prep

On paper, Rowing Blazers seems like it should be the most authentic prep brand ever. Its founder Jack Carlson graduated from a string of elite schools — first Buckingham Browne & Nichols, a top private school that sounds like a law firm and is located on the bank of the Charles River. After high school, he was accepted into Princeton, Cornell, and Georgetown, the last of which is where he completed his undergraduate degrees in Chinese and Latin. Then he left for Oxford to pursue his doctorate in archaeology (an experience so British, his graduate advisor Jessica Rawson even has the honorific title Dame). Upon graduating, he returned home to Massachusetts to teach Classics at St. Marks, an Episcopal, preparatory school located just outside of Boston.

Carlson’s heart, however, has always been in rowing, a sport he was introduced to in high school. He plays as a coxswain, the “coach” of the boat who sits at the stern, directing the rowers and helping them keep a proper rhythm. From 2011 to 2015, he represented the United States at three World Championships, winning a bronze medal on his last run. And in the final year of his doctoral program, he published Rowing Blazers, a book about the sport’s striped, trimmed, and badged jackets, as well as the stories, athletes, and historic clubs associated with them.

That book would later serve as the basis for a clothing line by the same name. Rowing Blazers supplies the official club blazers to various rowing, rugby, and social organizations — Princeton, Cambridge, UPenn, UVA, and Carlson’s alma mater, Georgetown, among them. “These clubs used to rely on one-man tailoring operations, and those tailors either retired or passed away,” Carlson explains. “So the clubs came up with makeshift solutions. Princeton’s rowing club, for example, just bought black suit jackets and had someone sew grosgrain ribbon around the edge. There’s something charming about that, but it’s also not ideal. We came in to fill that niche.” Some organizations have uniquely modern designs. For the women’s rowing club at the University of Texas, Rowing Blazers makes a hybrid jacket that borrows from cowboy jackets and rowing blazers. For the Lady Margaret Boat Club, where some say the word blazer originates, they continued with the club’s historic scarlet red garments, connecting today’s members to those of yesteryears’.

Carlson cares about authenticity, but mostly in the way that a social scientist would reference institutions. He says the brand’s starting point was “doing things the right way,” by which he means making club blazers from the “right materials,” using the “right factories,” and connecting them to actual organizations. “I spent five years researching for the book, so I had a big collection of vintage rowing blazers. At some point, I figured I should put them to use,” he says. “I hate it when I walk into Ralph Lauren and there are hats and polos with phony baloney crests, oars, and coats of arms. We make things with a club aesthetic that anyone can wear, but also club-specific items that are exclusively for those organizations’ members. There’s a real heritage connected to what we do. Ralph Lauren started with the name Polo because he wanted the brand to sound fancy — he didn’t actually play polo. We actually started by making blazers for rowing clubs.”

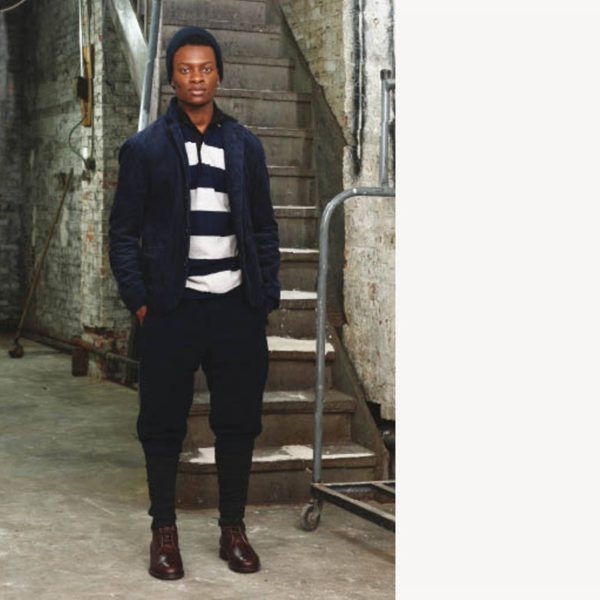

A lot of what Rowing Blazers sells looks like the sorts of things worn by people who can recite Brideshead Revisited word-by-word. They have embellished tennis polos, striped rugbys, and of course, unabashedly preppy blazers. At the same time, Rowing Blazers is very much the “classic with a twist” that rankles stuffed-shirt traditionalists. Their marketing campaigns feature young people wearing overlong belts, seersucker suits with graphic tees, and blackwatch shorts with matching suit jackets. The clothes are cut a little more modern, with shorter-than-usual jackets and ankle-cropped pants. For New York Fashion Week, Knicks forward Lance Thomas walked down a runway in a striped boating blazer that had been customized with pins and paint (the brand dressed other elite athletes, including David Robinson and Marcus Allen, for the charity event). And when Rowing Blazers collaborated with J. Press for an updated line of brushed Shetland sweaters, they took the Shaggy Dog label — which is usually hidden on the underside of the collar — and slapped it on the chest, like a civilian rank insignia or symbolic heart.

While not canonical in terms of their appearance, these things don’t seem that far from the spirit of prep, a style that came up with things such as go-to-hell pants, “fun shirts,” patchwork madras and tweed, critter embroideries, and novelty ties. To the degree that prep can be distinguished from trad, it’s always been the louder, more irreverent end of American style — a little more youthful and always smiling, its colors are brasher and styling more derisive. If neo-prep feels different, it’s partly because the world is no longer insular. Rowing Blazers draws heavily from streetwear, which has large overlaps with black and skate culture. The overlong belts you see in some of the photos above take their cues from how skateboarders used to style their Marshalls-sourced accessories in the 1990s.

Rowing Blazers also features a more diverse range of faces in their marketing campaigns, which has attracted a surprising (but also not that surprising) amount of negative attention. A couple of years ago, when Rowing Blazers sent out an email blast about a new product release, a rowing coach shot back, saying “this doesn’t look right to me.” “At first, I thought he meant the photo wasn’t loading,” says Carlson. “But after someone from my support staff emailed back, it became clear that he meant he didn’t think it looked right that two black models were wearing rowing-styled clothes. He said we were appropriating white culture.” Upset, Carlson forwarded the coach’s email to the college’s diversity department, along with a complaint letter. “I never heard back and he’s still coaching there.”

I asked Carlson if he consciously tries to make a white aesthetic look more diverse, hoping to clean the style of its elitist stigma. He pauses, then talks about how he doesn’t like the forced diversity in J. Crew and Ralph Lauren ads, saying they look phony (the idea of authenticity rears its head again!). “We don’t think, ‘OK, we need a black guy, an Asian guy, and a woman,’” he says. “Most of the people aren’t even professional models. They’re friends, Olympic rowers, or artists we know who have a cool look. But I also think, why would I put out an image that’s problematic? I’m actively trying to change people’s perceptions of who can be in rowing. As someone who was on the US team, I feel we’re not meeting our potential because we’re not tapping into huge groups of people who could be excellent rowers. That’s one of the reasons why I got involved with Row New York. It’s an academic and rowing program that serves kids from under-resourced communities. These are primarily black and Hispanic teams that are out there winning state championships, they’re qualifying for nationals. If we’re making blazers for Winchester College, why wouldn’t we also want to support that? Kids who go through that program are also more likely to go on to college, including top schools such as Columbia and Georgetown.”

The Authenticity of Production Versus Context

Last October, Harvard’s student newspaper The Crimson did a short feature on Amanda Zhang, a Harvard undergrad who was working on a project focused on modern-day Harvard student dress. Since the 1950s, Harvard and other elite universities have become a lot more diverse, both in terms of racial and economic background. In 2014, a record number of African-American and Latino students matriculated into Harvard, and today, less than 50% of the total student body is white. Zhang explained that, as the student body has changed, women and people of color haven’t always felt comfortable in the petite sundresses, Bermuda shorts, and boat shoes that used to be seen around the campus’ gothic arches and grassy knolls.

“When I think of my family in Asia, if you ask them, ‘What’s a good school?’, they will say, ‘Harvard.’ If you ask them, ‘What do Harvard students dress like?’, and they will say, ‘This,'” Zhang says in the article. The article continues: “While many conceive of the stereotypical Harvard professor as someone who prefers collared shirts and pressed slacks […] her professor regularly sported ‘jean overalls and Nikes to class as professional wear.'” For both students and professors, real life Ivy Style has changed.

The blog Ivy Style’s founder and main writer Christian Chensvold was derisive of the article in a Halloween post. “Darkness has fallen, the witching hour is upon us, and the boys from Take Ivy have rolled over in their graves, disinterred themselves, and become the walking dead, driven by the unholy urge to retake Ivy. Trick or treat!,” he wrote. Chensvold’s post touches on some of the tensions running through the prep community. Many of his readers want Ivy Style to be the exclusive province of rich white people, but then get mad when actual students — many of whom aren’t rich or white — reject the uniform because it doesn’t comport with their authentic selves. Moreover, there’s something strange about seeing Ivy outsiders — Chensvold and I included — dictate to actual Ivy students what constitutes “authentic” Ivy dress.

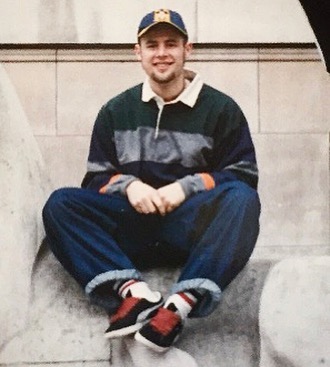

As online style enthusiasts, a lot of what we understand about prep comes from Take Ivy, which was originally published in 1965. It quickly became a cult classic and then underwent a lot of online marketing hype leading up to its re-printing in 2010. But unlike Zhang’s project, Take Ivy was never about sociology — it was about marketing. The photographer and filmmaker behind the book were working under the direction of the Japanese clothier VAN Jacket, who wanted real-life examples of Ivy League students wearing their preconceived notions of American campus dress. The whole point of the project was to sell an older version of Ivy Style to Japanese customers who valued authenticity. However, when they arrived, they found most students were dressed quite casually, so they had to be selective about who they photographed. Even still, most of the students featured in the book are dressed down because the authors could only fake it so much.

David Marx, who documents this history in his book Ametora, says there are really two types of authenticity. One is about how things are made (production) and the other is about how the clothes are used (context). “By not being a clothier on an Ivy League campus or Brooks Brothers, VAN Jacket was not an authentic Ivy League company. They made up for this, however, by emphasizing that the garments they made were authentic by a new definition: conforming to the exact specifications of Ivy League garments,” he explains. “This is what Japan contributes to the authenticity debate: not authenticity of context, but the authenticity of the production. And they were able to sell their clothes in Japan by saying, this is a popular style in the U.S. and we make the closest copies to what is available there. Authenticity of context is difficult in a globalized world, and it’s nearly impossible in the US where ‘Ivy League’ style only exists as a canonized set of practices, rather than the organic dress culture of Ivy League students. In our obsession with authenticity — which is key to our taste judgments — we still want authenticity, but the authenticity of context doesn’t really exist anymore. So we’re left with the Japanese version of authenticity — the authenticity of production.”

Prep Has Always Been Multicultural

We’re in the Age of Authenticity, where everyone wants to live an authentic life, eat authentic food, wear authentic clothes, visit authentic places, and vote for authentic politicians. But in menswear, and particularly prep, authenticity can only have meaning in production. The 1950s world of Ivy League campuses is long gone, save for a few bow tie wearers lingering at the Harvard Club in New York City. Most of the style’s adherents came into the look through the internet or a Ralph Lauren store. How many, after all, actual Old Money WASPs with Ivy League degrees do we suspect are reading the blog Ivy Style? On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.

The idea that Ivy Style is purely white is also a total invention, probably derived from ‘80s films about teenage struggles and rich dicks. In reality, Ivy has always been multicultural. Its fabrics and styles borrow from around the world: from India, we get madras, seersucker, and the beginnings of the button-down collar; from Indonesia comes batik; from China and the Philippines come khaki chinos; from Ecuador, we get Panama hats. The Jewish pedigree of this quintessentially American style is also undeniable, having been shaped by tailors and clothiers such as J. Press, Chipp, and Ralph Lauren. And while Ivy is most closely associated with the Ivy League schools on the East Coast, it spread West partly with the help of Black jazz musicians. For much of its history, trad was the lingua franca of menswear, worn by people of every political, ethnic, and class background.

Authenticity of production doesn’t have to be a straitjacket, either. Often times, prep gets renewed when someone finds new ways to wear an old item. “The way I think about it, the rugby has its origins in a posh British sport at a posh British school, Rugby. It’s one of the great British schools, like Winchester and St. Paul’s,” says Carlson. “But the rugby shirt also has a whole ‘nother history that often gets ignored. It’s been worn by different people in different ways, such as David Hockney and Mick Jagger. Benetton made rugbys; Tommy Hilfiger once collaborated with Coca Cola on a rugby. In the ‘90s, a lot of hip hop guys wore rugbys. It’s been worn by Tupac, Andre 3000, and Kanye. People who claim it as only for white, upper-class people are inventing history. The rugby is a lot more multicultural in real life.”

Since they opened their pop-up shop (which is now their flagship), Carlson says he’s seen all sorts of people come through the doors — classic menswear guys wearing Drake’s, streetwear heads coming in from Supreme, rappers, athletes, regular ol’ dads, and even the occasional rich preppy who gets dropped off by their driver. Rowing Blazers has become the acceptable face of prep for streetwear guys, and conversely the acceptable face of streetwear for preppies. If we really care about authenticity, shouldn’t the concept extend to people’s identities? Most people are multidimensional and have different interests. Carlson was on the US rowing team, went to Georgetown and then Oxford, and likes preppy clothing. At the same time, he studied ancient Rome and China in college, listens to hip hop, reads HighSnobiety, and follows sneaker drops.

“I think young people are increasingly rejecting the traditional tribes,” he says. “It’s like that Ferris Bueller scene, where Grace says ‘motorheads, geeks, dweebies, dickheads.’ Of course, tribes still exist, but increasingly people can pull from different worlds and find what they like without being defined by whole categories. Dan Fox, who wrote Pretentiousness, calls these people cultural omnivores. I think that term really describes my generation. Maybe someone went to prep school, but they also read Hypebeast. Perhaps they didn’t go to college at all, but love preppy clothes. People are into all sorts of things that you may not expect. And there’s more interest in wearing something if it doesn’t feel like you have to be in a specific club to wear it.”

(Thanks to Jack Carlson and David Marx for talking with me for this post. And while Rowing Blazers is a sponsor on this site, this isn’t a sponsored post. As always, we don’t do that kind of stuff).