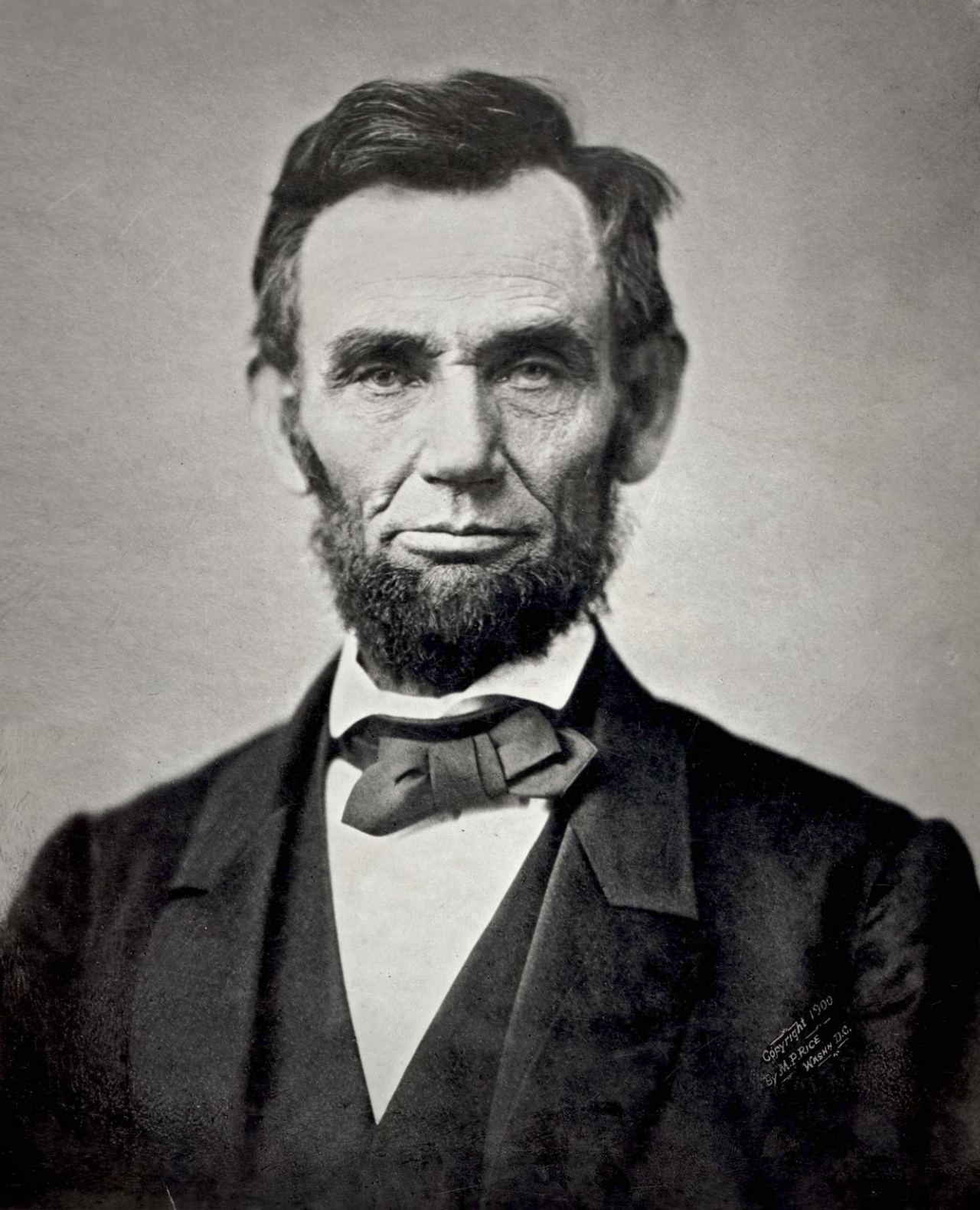

The Appendix has a great story about Abraham Lincoln’s famous beard (or “whiskers,” as writers of that time would say). He grew it a few weeks before his inauguration, supposedly on the advice of Grace Bedell, an eleven year old girl who wrote him a letter during his campaign. An excerpt from the article:

Rather, Lincoln’s whiskers were meant to signify urbanity and refinement. Adopting a fashionable style of grooming—the wreath of whiskers that had been a fixture of men’s fashion for decades—Lincoln offered a visual counterpoint to persistent barbs about his rough manners, rural upbringing, and rustic sense of humor. Holzer, then, was at least partly right about the meaning of Lincoln’s whiskers. He was, in fact, shedding the campaign image of the frontier railsplitter. But instead of adopting the look of a firm patriarch (or even a stern sexton), he was cultivating the appearance of a man of the world: a person of humble origins but hard-earned cultural capital.

He had good reason to do so. Since assuming the national stage, Lincoln had been dogged by doubts about his social graces. An article from the Columbus, Ohio Crisis, for instance, lampooned his ignorance of classical languages, while informing polite readers that Lincoln had only recently “abstained from facetiously designating hotel napkins as towels.” And one contemporary, recalling an encounter between the former Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft and Lincoln noted a “most striking” contrast between the two: “the one courtly and precise in his every word and gesture, with the air of a trans-Atlantic statesman; the other bluff and awkward, his every utterance an apology for his ignorance of metropolitan manners and customs.” Eager to dispel these aspersions—especially in light of unfavorable comparisons between himself and the stately Jefferson Davis—Lincoln grew fashionable whiskers, not a patriarchal beard.

What does this story tell us about Old Abe Lincoln? Besides the obvious—that the “most famous beard in American history” was not a beard at all—it reveals something about the nature of power in Civil War-era America. Taking command of a sinking ship of state and confronted with dire questions about his fitness for office, Abraham Lincoln chose a set of symbols that emphasized urbanity over more obvious emblems of authority. Calling on an old set of ideas about gentility and power, the president-elect claimed, in effect, that the right to rule hinged as much on politeness as on patriarchal strength or the imprimatur of the people. It’s a strange story, to be sure. But it reminds us of the extraordinary currency of symbols like these: that faced with national dissolution and civil war, Lincoln sought the urbane sophistication required for his job in, of all places, his hair.

You can read the full story at The Appendix.

(Story found via IQ Fashion)