Beat: a word used to describe a group of people, mostly poets, who had in common a general rebellion against the restrictiveness and false sheen of post-World-War-II American society. Also used to describe things that have been done to death. A post on beat poet style? Beat.

But I want to look past the obvious handsomeness of writers like Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, whose blue-collar shirt’n’pants style looked good on them in much the same way most clothing looks good on good looking men. And who also have had their style reps burnished by dying relatively young, so the images they leave behind are of youth and charm–fabulous roman candles exploding, etc. I want to get a little weirder, with Allen Ginsberg.

Allen Ginsberg’s Path to Beat-ness

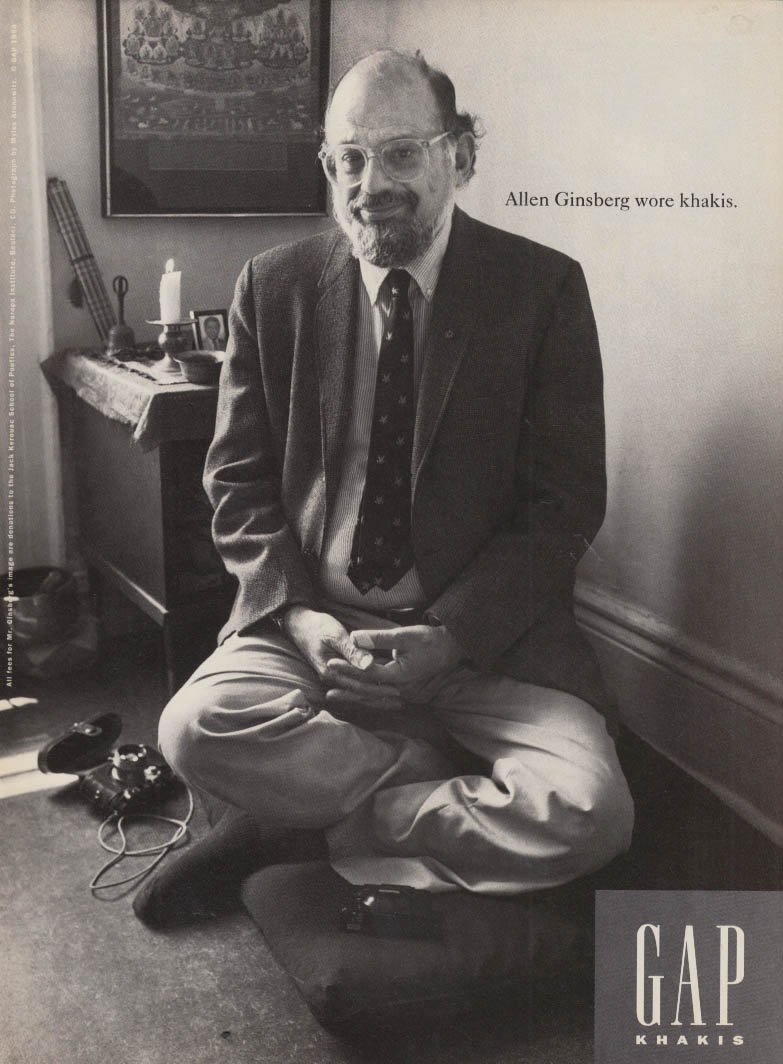

Allen Ginsberg started out on a path post-war society might consider respectable. The son of a published poet, he studied literature and met some other proto-beats at Columbia University, graduating in 1946. He took a job on Madison Avenue in the advertising industry. A few years of commercial work disillusioned Ginsberg, though, and he moved to San Francisco, intending to write. (not sure how he felt about the GAP ad in which he featured.)

He made his mark with Howl, a long, Walt-Whitman-esque lament for his generation that’s become one of the most widely read verses of the 20th century. Howl is confessional, obscure, lyrical, angry, funny, and dirty; its publisher was tried for obscenity, but the state lost its case, making the poem and Ginsberg a national sensation.

I’m not going to get into deep “what does this all MEAN” analysis here, but in the poem, Ginsberg seems to pretty clearly refer to his stint as an ad man with the line “who were burned alive in their innocent flannel suits on Madison Avenue amid blasts of leaden verse & the tanked-up clatter of the iron regiments of fashion.”

Rebel Style, of a Sort

A minor point in a major poem, to be sure. But it marks Ginsberg’s break with the establishment as defined by its uniform of flannel suits and its service of fashion. Post-flannel-suit, Ginsberg did not adopt the workwear style of his fellow beats, necessarily; his style was marked more by mismatched suit pieces he bought secondhand, tunics he brought back from trips abroad, and public nudity. He had a reputation for taking off his clothes at poetry readings. His other defining characteristic was his glasses, often thick-framed; dark in his younger years and mostly clear- or wire-framed as he got older.

Ginsberg’s shabby clothing was part of his broader effort to confront polite society — his work was critical of American values, or at least America’s faithfulness to its stated values. He was also gay and out; not common in the 1960s. He was a practicing Buddhist and a self-professed communist. He seemed to find shocking his audiences quite enjoyable.

Ginsberg’s Secondhand Style

In photos, especially after the 1950s, Ginsberg’s clothing tends toward the absent minded professor in a way that’s not, on the surface, inspiring. (As a guy who studied English at a liberal arts college, the look is very familiar.) Suits and shirts of questionable fit, cheap looking ties, trousers and shoes of unclear intentionality. But I think Ginsberg’s dedication to this sort of thrift shop anti-style presaged the thrift/vintage movement that was gathering steam everywhere in the 1960s, and maybe even more so in the postmodern, DIY style of the 1980s and 1990s. Take things cast off by society and put them together in your own way.

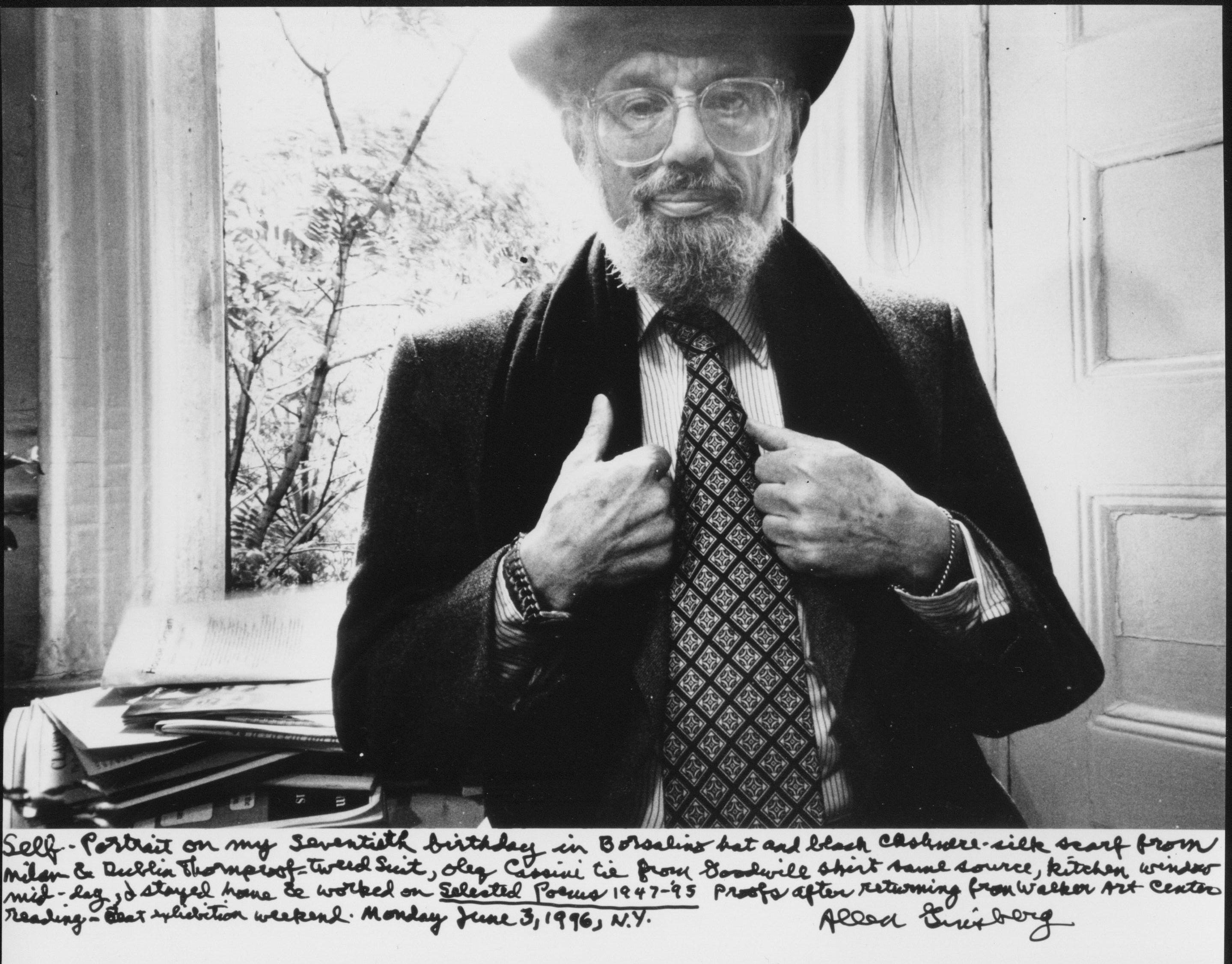

And there are hints that the scattered nature of Ginsberg’s style does not indicate a lack of interest in clothing. First off, he didn’t have to wear a jacket and tie –most of his contemporaries did not — but he often did so. One piece of evidence comes from a 1996 self portrait. He was a good photographer, and annotated many of his prints. This print bears a clothing-specific caption:

Self-portrait on my seventieth birthday in Borsalino hat black cashmere-silk scarf from Milan & Dublin Thornproof-tweed suit, Oleg Cassini tie from Goodwill shirt same source.

First off, I think he looks pretty great here. And there’s a story behind that suit. In October 1993, Ginsberg went to Ireland and read poetry at Dublin’s Liberty Hall, for a crowd including Bono (this is when Bono was awesome). In interviews with the Irish press, he said he came to London because a poetry editor there had promised that, if he did, the editor would buy him a new tweed suit.

“after a little shopping around, [the editor] found that Kevin and Howlin tailors on Nassau Street did a variety of the ‘thornproof’ tweed and it was there that Ginsberg was outfitted. The irony of the company’s name wasn’t lost on him either.”