- Oscar Wilde’s Shirt

- Lounge suits worn by the Duke of Windsor (left) and Dr. André Churchwell (right)

- Banyan belonging to George, Prince of Wales (circa 1780s)

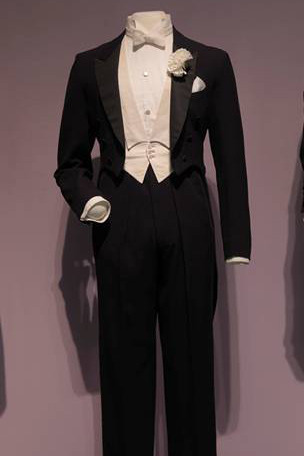

- Fred Astaire’s Anderson & Sheppard tuxedo

Within the space of a few years at the turn of the 19th century, Beau Brummell revolutionized men’s fashion, replacing draped and colorful silk finery with simple, dark wool garments tailored close to the body. He found elegance in austerity, emphasizing fit and cleanliness over luxury and excess. The new style brought together the costume of horseback riding and the military to create a new urban fashion, and vaulted Brummell to personal celebrity. Brummell, and the legions of admirers and imitators that followed every fold of his cravat, became known as “dandies.” The Rhode Island School of Design’s recent Artist, Rebel, Dandy exhibit explored the history of the dandy, starting with the Brummell’s elegant simplicity and finally exploding into the extravagances that the word “dandy” calls to mind today.

Dandies aspired to “poise, a hint of disdain, even a touch of mischief,” as Hugo Vickers Muses describes the style of early 20th century dandy Cecil Beaton in the exhibit book. Others saw only farce. The exhibit includes caricatures from Brummell’s time that show dandies corsetting and cinching themselves into fainting spells to achieve the proper silhouette. But by the last half of the 19th century, Brummell’s revolution had codified into a set of rules that no proper English gentleman would dare violate.

The mid-to-late-20th century pieces in the exhibit show dandyism aging gracefully, experimenting with tweed suits from Luciano Barbera and the late RISD professor Richard Merkin, and plaid suits from with Italian industrialist Gianni Agnelli and Tennessee doctor André Churchwell. But by the time we reach the outfits of modern dandies, Brummell’s elegant simplicity has been completely inverted. The denouement is Sebastian Horsley’s red velvet suit, complete with matching two-foot-tall red velvet topper and bedazzled jumbo-knotted tie. Whereas Brummell proclaimed, “If John Bull turns around to look at you, you are not well dressed…,” Horsley warns that “the real dandy wants to make people look, be shocked by, and even a little scared by the subversion which his clothes stand for.”

Perhaps we should mourn that Scott Schuman considers the dandy “more obvious, more flamboyant, almost aggressive” compared to the “quiet seduction” of Luciano Barbera, whom he profiles in the exhibit book. It wasn’t meant to be this way. But sadder still is the idea that clothes so completely make the man. Horlsey believed that “dandyism is a lie which reveals the truth and the truth is we are who we pretend to be.” Clothes are a powerful vehicle for self-expression and self-discovery, as well as a sensual pleasure. At their best, they are our cover letter to the world. At their worst, they are a prosthesis, a false self to replace the one we don’t know or don’t like.

Though “dandy” may have become be a dirty word, male interest in clothing and style is currently surging. Artist, Rebel, Dandy shows all the beauty, elegance, and absurdity that could result.

Guest post by our friend David Isle, who authors the blog Ivory Tower Style. Photos from the Rhode Island School of Design.