Conversations about menswear writing kept coming to the same book: Anne Hollander’s Sex and Suits: The Evolution of Modern Dress. Though led by a promising title, the content comes as something of a surprise. While enlightened enough to realize that a woman can, possessed of inherently fresh perspective, put together a men’s style book, I wouldn’t expect it to take this form. Sex and Suits has less in common with Cally Blackman’s highly visual 100 Years of Menswear, which primarily shows, than with Nicholas Antongiavanni’s thoroughly textual The Suit, which (in the male manner) primarily tells. Yet like fashion historian Blackman, art historian Hollander has an interest in the evolution of dress, and like Antongiavanni, she centers her analysis around what we today call the men’s suit: how it came about, how we wear it now, and what may become of it in the future.

We live in that future, since Sex and Suits came out in 1994. A curious age: the suit hardly enjoyed a heyday in mid-nineties America, nor do we look back to that era for high watermarks in other areas of men’s dress. But Hollander acknowledges writing at the suit’s low ebb, seizing the moment for Gauguin-ish reflection: where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? She asks not just on behalf of male dressers, but for females as well, dealing with both sex and suits by tracing the relationship of men’s and women’s fashion from the seventeenth century to the then-present, a tale of separation, envy, imitation, and, finally, a new exchange. She establishes early on her sense of “something perpetually more modern about male dress that has always made it inherently more desirable than female dress.” She cares not about its supposed status or power, but “a certain fundamental esthetic superiority, a more advanced seriousness of visual form.”

Did these once sound like fighting words? Recall the tetchy, confusing climate of Political Correctness hanging over that time, which beset academia with a special aggression. Though Hollander writes as an independent scholar, her fellowship at the New York Institute for the Humanities presumably put her within its striking distance. Innocuous as they sound today, I imagine her claims about the visual solidity and integrity of menswear against the decorative ephemerality of women’s wear drew serious charges of self-hatred. But the book itself gives less a sense of judgment than diagnosis. “The advance of restraint as a quality of male dress may well have been hastened, spurred by the extremity of ladies’ fashionable excesses,” she writes of late eighteenth-century Europe’s Great Male Renunciation, when men gave up elaborate beauty for studied sobriety, leading over the following century to the dominance of the suit, “of which the folly could only be something sane men should be clearly seen to avoid, even if they liked it on the ladies.”

Alas, the clear-thinking Hollander at times displays symptoms of another, prose-debilitating academic affliction of the nineties. A fair few of the sentences in Sex and Suits suffer from the same leaden passiveness as that quoted above, giving the impression of a book straining, against its own material, for dryness. These 199 pages whose subject matter could hardly fit more neatly into my interests thus took weeks to read. If you’ve grown used to taking your men’s style information through photographs and illustrations (of which latter Sex and Suits has a few, mostly depicting movements in men’s fashion far out of living memory), you may put the book down and not pick it up again. But stick it out, since Hollander, even in her cloudier moments more lucid than the classic “bad academic writer,” offers insight into not just the origin of the male suit and its relationship to the less formal clothes we wear today, but by way of a running comparison with women’s wear, into its aesthetic advantages — and its pleasures.

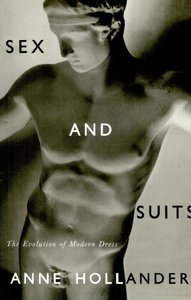

Hollander sees the suit using “strong, simple forms of modern design perceived as naturally masculine” and “an established set of formal rules, like classical architecture.” Her history places one of the suit’s feet, if you will, in the forward-thinking present, and the other in antiquity’s search for universal, eternal principles. The cover’s nude, colorless Greek statue represents this conception of the suit more accurately than any garment could. Where some call suits inexpressive, Hollander responds that “they express classical modernity, in material design, in politics, and in sexuality. In their pure form, they express a confident adult masculinity, unflavored with either violence or passivity.” Just over a decade later, our suit-reviving era would begin. Mad Men, whether bellwether or cause, has put the word “modern,” with regard to menswear, back on our lips. When we say it, we mean not just what looked modern in the show’s early-sixties America, but what also looks equally modern now — just what those ancient Greeks sought after.

Many well-dressed men I know still lament the Great Male Renunciation, but I, with a bent for sartorial modernism, feel less broken-up. Sex and Suits deepens that bent, but we live in a good time for it, and I imagine Hollander would approve of the influence across menswear the suit has regained. Yet we also live with the legacy of the freeform “postmodernism” she describes around her: a “pulsating tide of mixed influences,” “the headwaiter in black tie and dinner-jacket,” “the patron in denims, sweatshirt, and running shoes,” and no requirement “to respect the occasion itself in prescribed ways.” That formality vacuum remains, and Sex and Suits encourages treating it not as a loss, but an opportunity: “We must make up our own version of what the occasion requires of us personally — which everyone can then observe and judge.” If we read books like Hollander’s attentively, they suit us, as it were, to meet the challenge.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall. To buy Sex and Suits, you can find the best prices at DealOz.

More men’s style books: Preppy by Jeffrey Banks and Doria de la Chapelle | The Nordstrom Guide to Men’s Style by Tom Julian | 100 Years of Menswear by Cally Blackman | The Suit by Nicholas Antongiavanni | ABC of Men’s Fashion by Hardy Amies | Off the Cuff by Carson Kressley | Take Ivy by Teruyoshi Hayashida et al. | Icons of Men’s Style by Josh Sims | The Details Men’s Style Manual by Daniel Peres | The Men’s Fashion Reader by Peter McNeil and Vicki Karaminas | Dressing the Man by Alan Flusser