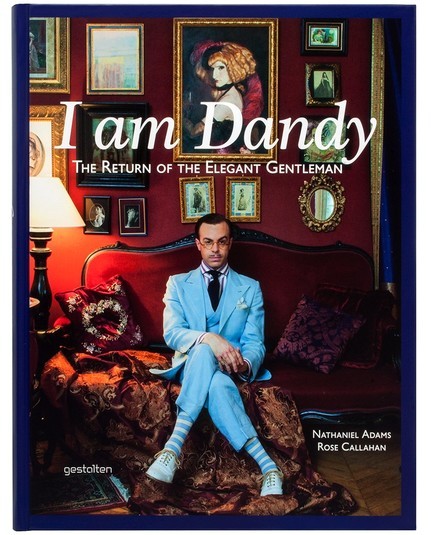

I Am Dandy: The Return of the Elegant Gentleman consists of 56 profiles of well-dressed men. Each one names the place of birth, current location, and occupation of the profiled. The first varies, the second tends toward the predictable urban suite of New York, London, and Paris, and the third includes such implausible careers as “creative advisor,” “flâneur,” “boulevardier,” “professional bohemian,” “reality escapologist,” and “editor.” Luminaries referenced in the interviews include Quentin Crisp, Stephen Tennant, and Sebastian Horsley. If you can’t put faces to those names, or can’t imagine the actual pursuits some of those lifestyles comprise, you fall squarely on one side of the many debates surrounding dandyism currently roiling on the internet, usually in quarters some distance from Put This On: should a dandy work, or should he live for elegance and leisure?

You may wonder what becoming a dandy — commonly understood as a man who wears, deliberately, the finest clothes he can, without fear of standing out — has to do with not having a real job. According to some of this book’s dandies, they have little to do with each other; according to others, for whom crafting and refining the presentation of themselves and their surroundings adds up to much more than a full-time gig, they have everything to do with each other. Writer Nathaniel Adams and photographer Rose Callahan teach the controversy, if you will, placing the consummately self-styled writers (Gay Talese makes a notable and unsurprisingly dignified appearance), wine buyers, filmmakers, musicians, brand managers, and businessmen alongside figures whose sources of income remain as mysterious as their biographical details, sexual orientations, makeup-free faces, and given names.

I’ve already called the men of I Am Dandy “well-dressed,” and though most readers would, broadly speaking, agree, I may revise that, slightly, to “consciously dressed” — men, as Esquire “Style Guy” Glenn O’Brien puts it in his foreword, “who share a certain eloquence in the language of clothes.” Employed or not, and whatever their aesthetic-philosophical stance, these guys all put a great deal of energy into developing and dressing in a manner ideally and only suited to themselves. For some, this means mastering their particular version of the Ivy look; for others, surrounding themselves (in terms of clothing as well as anything else controllable) with detail-perfect recreations of Regency London or the Charleston, South Carolina of 1920. Some stylistic missions fall in the middle; I think especially of the striking example of one Barima Owusu Nyantekyi, who pays tribute to his Ghanian heritage with suits of the late 1960s and 70s, menswear’s “dark ages.”

But how much of everyday use can we learn here? In the case of, say, “Dandy of New York” Patrick McDonald, known as much for his painstakingly applied eyebrows as his wardrobe, the knowledge would seem rather specialized. But the comparatively restrained Christian Chensvold, editor of Ivy-Style.com; Nicholas Foulkes, writer on menswear and much else; Nick Sullivan, Fashion Director at Esquire; the perhaps shockingly H&M, Zara, and Uniqlo-clad Winston Chesterfield; or even the more daring Minn Hur and Kevin Wang, proprietors of men’s suiting company HVRMINN, dress in ways Put This On readers could do well to adapt for themselves. More visual and textual space tends to go to the obvious eccentrics, but even they, when you get over their walls of Wildean pronouncements, say much worth bearing in mind.

To take a sterling example from one of the bolder yet somehow less flamboyant case studies, a Harlem bandleader named (yes) Dandy Wellington: “Dressing above your station is like physically talking out of turn. You need to prepare yourself for the position you want. And it becomes the position that you’re in.” Sound superficially though this may like the standard advice to “dress for the job you want, not the job you have” (or the blunter but more useful “fake it ’til you make it”), Wellington’s statement gets at the dandy’s insight that, through stylistic choices in clothes and elsewhere, one creates one’s own self-fulfilling reality. You yourself may have no interest in passing day after languorous day amid the vintage curios filling your Queens apartment like a creature out of Brideshead Revisitied, but if you don’t have some kind of an envisioned lifestyle to realize, where has your ambition gone?

True, the aggressive antiquarianism on display in much of I Am Dandy can tire — when I got to the barber who “drinks from a mug with a special rim designed to keep his mustache dry,” I almost gave up — and when confused with the simple pursuit of quality, mislead. Luckily, O’Brien’s bracing words, a defense of hardworking dandyism where “conspicuous self-employment” replaces “conspicuous consumption,” set you in good stead to interpret all the peacock displays, with their varying vividness of plumage, to come. “I do not believe in making a spectacle of myself,” he writes, distancing himself from what dandyism has become “in an age of street fashion blogs.” “I do believe in being interesting on further inspection, but I prefer to use the streets with some anonymity. Elegance derives from the Latin, eligere, to select, to choose with care, and that’s not something that one can determine from across the street.”

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, aesthetics, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter @colinmarshall or on his new Facebook page. To buy I Am Dandy, you can find the best prices at DealOz.

More men’s style books: Fuck Yeah Menswear by Kevin Burrows and Lawrence Schlossman | Sex and Suits by Anne Hollander | Preppy by Jeffrey Banks and Doria de la Chapelle | The Nordstrom Guide to Men’s Style by Tom Julian | 100 Years of Menswear by Cally Blackman | The Suit by Nicholas Antongiavanni | ABC of Men’s Fashion by Hardy Amies | Off the Cuff by Carson Kressley | Take Ivy by Teruyoshi Hayashida et al. | Icons of Men’s Style by Josh Sims | The Details Men’s Style Manual by Daniel Peres | The Men’s Fashion Reader by Peter McNeil and Vicki Karaminas | Dressing the Man by Alan Flusser