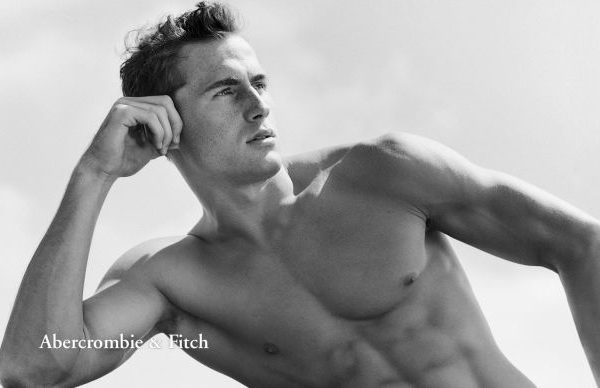

As A+F embarks on rebranding itself in a post-Mike-Jeffries, post-cargo-short environment, writer Alex G. Frank examines his complicated affection for the handsome, vapid A+F of the 1990s mall (itself a rebranding of an old hunting outfitter).

Much of this shift is a sign of progress. Increasingly, it seems that the days of Abercrombie’s offensive slogan tees and discriminatory hiring practices

are behind it. It’s promising for a company to abandon its “cool”

elitism in favor of opening itself to everyone, an indication perhaps

that the world is in a better place than it was when Abercrombie’s body

shame-inducing ads — famously featuring the young, beautiful and naked

frolicking on docks with footballs in hand — and all-American whiteness

were seen as selling points as opposed to oppression.

The

old Abercrombie symbolized, more than anything, popularity — a trait

that eluded me in my middle school days but that I was, like so many

kids, obsessed with. The feeling that Abercrombie was meant for some

better class of people than me was both punishing and promising, that

strange American brew of self-hate and self-love, longing and ambition,

that drives consumerism.But even if the old Abercrombie didn’t always encourage the best impulses in my adolescent life, at least it incited something.

To want to be somebody is at the very core of American capitalism. We

shop to become the person we hope we are, dress for the job we want, and

Abercrombie sparked those kinds of feelings in me, waking me up to the

possibility of different ways to live and present myself. This new

Abercrombie, with its normal clothes that whisper rather than scream,

says something else: Blend in, be humble, don’t make any sudden

movements.It is, alas, a new Abercrombie for the same old us.

–Pete